The Inflation Reduction Act for the first time allowed Medicare and Medicaid to negotiate with drugmakers for pharmaceutical prices. It also contained a much less discussed provision regarding patent protections. The law sets different exemption times for “small molecule” drugs that can be taken in pill form and “large molecule” ones that have to be injected or infused. This has the potential to change the structure of incentives for the Pharma industry and not necessarily in a way that benefits patients.

The byzantine US market and pharmaceutical prices

It has been quite a while since George Merck in 1950 declared “We try never to forget that medicine is for the people. It is not for the profits. The profits follow, and if we have remembered that, they have never failed to appear. The better we remember it, the larger they have been.” Today’s pharmaceutical companies bear little resemblance to the chemicals-based organizations on which the sector was originally founded. But the way in which drugmakers make money can be extremely convoluted to understand, particularly the way they make money in the United States, the world’s richest market.

In a normal market, providers offer a product or service and price it for the value it believes it represents to the customer. A customer either agrees or not and eventually in a successful transaction, prices are set that both sides can live with. Branded pharmaceuticals are a whole ‘nother thing. As I pointed out in an article on insulin, it is astonishing that a 100 year old product has seen prices rise steadily, to the point at which one study found that obtaining the life-saving drug was an extreme financial burden to the 14% of Americans who need it to stay alive.

Part of the reason this is possible is that drug companies are granted patents on treatments, essentially a temporary monopoly to let them recoup their R&D investments. Those temporary monopolies are very sweet, prompting lots of strategies to extend them through a variety of practices that have come under heavy criticism.

Drug pricing in America is the product of decades of convoluted dealmaking, beginning with the manufacturers, who argue that they need high prices to pay for the R&D that creates miracle drugs in the first place. There are essentially no regulations around what a pharma firm can charge for a new drug, leading to eye-popping prices, such as Gilead Sciences $84,000 / price tag for a full course of its 2013 release of hepatitis medication Sovaldi.

While that sounds pretty high, remember that the drug cured Hepatitis C, preventing disease progression in people who might have gone on to require liver transplants or other expensive treatments. Gilead argued that the high price was needed because they had to recoup the investment they made to find the cure, and a curative drug is less lucrative than a drug that has to be taken on an ongoing basis. Observers argue that the company was motivated by profits, rather than providing the drug to the greatest number of patients who could benefit from it.

The morphing role of pharmacy benefit managers

But here’s where it starts to get weird. The price of a drug that you can find out about is the “list price.” Sort of like the sticker price on a car. The manufacturer then negotiates extensively with Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBM’s), who negotiate on behalf of insurers and payers. The original idea behind PBMs was that they would remove administrative burdens from insurers and the plan sponsors who actually pay for the whole system. Since that fairly innocent early idea, PBMs have become incredibly powerful, making much of their money on rebates that they negotiate. To appease them, many manufacturers raise the “list” price and offer a bigger rebate, which is unfortunate for those who actually do have to pay the list price.

Amazon is among the first retailers to offer transparent pricing, providing the retail price of a drug covered to, the price you’d pay if you did the whole thing on Amazon.

This is a totally different system than that of most other developed countries, in which national health systems are allowed to negotiate with manufacturers. One result is that pharmaceutical spending in the US is astronomically higher than in other comparable countries. And, in a uniquely American twist, when prescription drug benefits were added to Medicare under a 2003 law, Congress specifically forbade the two large public payers from negotiating, instead implementing a sort of “most favored customer” clause, as Brandenberger and Nalebuff discuss in their book “Coopetition.” Rather than leading prices to drop, the clause effectively gave pharmaceutical companies an out when other players tried to negotiate hard, basically by saying they couldn’t afford to offer discounts to the two biggest payers!

But things are about to change – a little

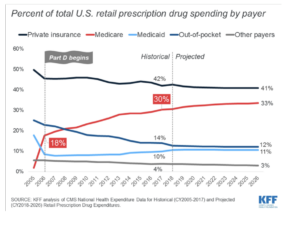

The Inflation Reduction Act essentially ends the most favored customer clause on a few drugs, granting the Secretary of Health and Human Services the power to negotiate prescription drug prices for Medicare patients. Part of the push to accomplish this has to do with the worrying growth of spending on pharmaceuticals after the benefit was offered under the Medicare Part D prescription benefit. It now stands at 18% of total pharma spend, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The right to negotiate has gotten a lot of press attention. But another shift, embedded in the Act, may prove equally important for the health and well-being of Americans and for the investment decisions made by leaders of major pharmaceutical firms.

This is that the Secretary of Health and Human Services can begin to negotiate pricing for drugs after a window of exclusivity for 9 years (for so-called small-molecule drugs that you typically take in pill form) and 13 years for large-molecule drugs (that have to be injected or infused).

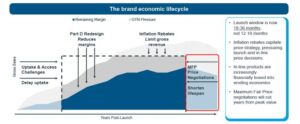

What that means, in turn, as an analysis by IQVIA points out is that the lifecycle during which a pharmaceutical company can enjoy what is essentially a monopoly is going to be truncated. This great graphic shows how much:

As Luke Greenwalt, author of the IQVIA analysis points out, one response on the part of the sector is that “manufacturers will look for products that face less impact by the Inflation Reduction Act. Increased focus on younger patient populations, large molecules, and rare and orphan diseases will mean that many products or indications that could benefit patients will not be pursued.”

In plain language, that means that plans and programs with a shorter exclusive “expiration date” are likely to be de-emphasized by pharma decision-makers, which is problematic as these drugs are often more convenient for patients and are easier to deliver.

Nonetheless, pharmaceutical companies are doing very nicely, thank you, with higher profitability than companies in other industries.

But there are cases when payers take control

Rather than putting itself at the mercy of Pharmacy Benefit Managers, Caterpillar’s Todd Bisping has been able to tame the growing cost of prescription pharmaceuticals. As I wrote about in Seeing Around Corners, following his guidance could create a watershed for payers, who seem to have the least amount of control over the system, despite the fact that they are the ones footing the bill.

As Todd says, “Start by eliminating waste in healthcare. I define “waste” as any penny more than we need to spend to get the optimal outcome for the employee who needs care. If we could spend a dime to help get someone healthy, and we spend a dollar, then we just wasted 90 cents on the same outcome. If you focus on finding places where there’s waste in healthcare, then you can squeeze all that waste out. That’s what we were able to do at Caterpillar: We found the waste and eliminated it, and that allowed us to maintain expenses without increasing costs for employees.”

Bisping found a morass of conflicts of interest, costs, and practices that did nothing to benefit Caterpillar while offering healthy profits to its PBM’s, to the extent that he estimated that 10-20% of Caterpillar’s spending did nothing to keep its employees healthy.

It will be interesting to watch how manufacturers respond to this shift in governmental policy, in terms of which drugs get the green light. As they make portfolio decisions, perhaps it would do everybody good to remember George Merck’s admonition that medicine is for the people, not the profits.