Some settings create ripe conditions for a business-model destroying inflection point. Unhappy customers, favoring one stakeholder group at the extreme expense of others and operating in such a way that even your allies can’t defend you are all early warnings that change is afoot.

In my 2019 book Seeing Around Corners, I used the case of the hearing aid industry as an example of how a whole sector could become subject to a major inflection point. The way in which hearing aids were regulated created massive unintended negative consequences. Because providing them was essentially a monopoly, they were too expensive for many people (and not covered by health insurance). Providers were restricted to a just a few, and at the time only six manufacturers produced them, with high margins and markups. Only one in five patients who could benefit from one were able to buy one.

My argument was that eventually such a situation would reach a breaking point, which it finally did in 2021 after a long and grinding battle by advocates for the hearing-impaired to allow over-the-counter sales of devices. This shift, experts predict, will reduce the cost of the devices and expand the number of providers in the market, while smart regulationsmake sure that they conform to essential standards of quality.

Where might we see similar dynamics play out in other markets?

What was the recipe that eventually led to the over-the-counter regulations on hearing aids? A large, underserved population that was barred from a desperately needed solution. Sufficient people in that self-same population so that most ordinary people had personal experience with the costs of a poor solution (“Dad, you really need a hearing aid!”). Technology that was no longer patented, in which the investment in innovation had long ago been repaid. Gatekeepers with little incentive to give up their chokehold role in distribution. An increasing lack of support from stakeholders for the status quo, meaning a bipartisan solution was pretty straightforward to iron out. And very sad stories about what happens to people afflicted with the condition.

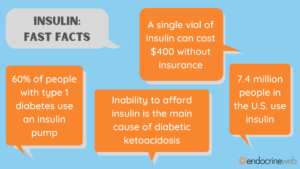

Which brings us to the question of whether there are other markets with these conditions that might also be ripe for a regulatory change which would increase access, affordability and competitiveness in the sector. One which is gaining increasing attention is the market for insulin, particularly in the United States.

Diabetes care – a new battleground for incumbents?

As defined by the Center for Disease Control, “Diabetes is caused by the body’s inability to create or effectively use its own insulin, which is produced by islet cells found in the pancreas. Insulin helps regulate blood sugar (glucose) levels – providing energy to body cells and tissues.” Without insulin, cells can’t function, basically. As one provider explains,

There are two main types of diabetes: type 1 and type 2. Both types of diabetes are chronic diseases that affect the way your body regulates blood sugar, or glucose. Glucose is the fuel that feeds your body’s cells, but to enter your cells it needs a key. Insulin is that key. People with type 1 diabetes don’t produce insulin. You can think of it as not having a key. People with type 2 diabetes don’t respond to insulin as well as they should and later in the disease often don’t make enough insulin. You can think of it as having a broken key. Both types of diabetes can lead to chronically high blood sugar levels. That increases the risk of diabetes complications.

For Type 1 diabetics, regular injections of insulin are the only way they can manage the disease, since their bodies don’t produce the hormone. For Type 2 diabetics, a lot of work has gone into figuring out whether the condition can be treated by improved diet and exercise, but many still require treatment.

A large, underserved population barred from a desperately needed solution

Diabetes is on a growth trajectory in much of the developed world. In the United States alone, the Center For Disease Control (CDC) reports that 34.2 million people, or 10.5% of the total population, suffer from the disease. It affects people from all social, economic and ethnic backgrounds. By comparison, about 30 percent of the United States populationsuffers from hearing loss, so diabetes is not quite as prevalent, but 34 million people is still an awful lot of people.

So, how well are these folks being served by the incumbent system? Not very well at all, it seems, at least in the United States. As Fortune’s Geoff Colvin points out, “Insulin in the U.S. costs on average some 800% more than in other developed economies. And yes, people die for lack of it, sometimes within days or even hours of missing their dose. No one knows how many; data suggests that in the U.S. it’s at least a few every day. Far more may suffer other ravages of diabetes—blindness, heart attacks, loss of limbs.”

A recent analysis found that almost half of all diabetics skip medical care of some kind due to costs.

Technology that is no longer protected and in which innovation investment has been repaid

Sir Edward Albert Sharpey-Schafer (1850 –1935), a British physiologist, first conjectured that a substance he called “insuline”must exist and play a role in the disease known as diabetes mellitus in the 1880’s. Some years later, in the early 1920’s, Frederick Banting and Charles Best, working under the directorship of John McLeod at the University of Toronto, with the assistance of James Collip, figured out how to extract and purify insulin in 1921.

On January 23rd, 1923 Banting, Best, and Collip were awarded the American patents for insulin. They sold the patent to the University of Toronto for $1 each. Banting notably said: “Insulin does not belong to me, it belongs to the world.”

Dr. George Clowes, then head of research at Eli Lilly attended a presentation (by all accounts a badly botched one) made by Banting on his research on insulin. Shortly thereafter, Eli Lilly obtained the rights to manufacture the drug for the American market (after some dicey negotiations with a Canadian firm that also wanted the rights). The product came to market in what was then lightning speed, beginning to sell quantities of insulin in 1923.

The existence of insulin was literally a life-saving change for Type 1 diabetes sufferers. Prior to it, the only treatment that prolonged life at all was starvation. It was a truly miraculous discovery.

And yet, it has been a hundred years since the original innovation. So why is it still so expensive and out of reach for so many people who need it?

Part of the answer is that, just as with hearing aids, a regulatory regime that was thought to be beneficial to public health has had the unanticipated consequence of reducing access to those who desperately need the solution.

In a study conducted by Johns Hopkins internist-researchers in 2015, Green and Riggs cite the practice of “evergreening” – adding incremental improvements to treatments that can themselves be patented with respect to the manufacturers of insulin. To stave off generic competition, these tactics kept insulin under patent protection for over 90 years, allowing these manufacturers, just like the makers of hearing aids, to have essentially monopoly control over the production and distribution of the drugs. And just four companies – Eli Lilly, Sanofi, Novo Nordisk, and Pfizer, own these patents.

Gatekeepers incentivized to retain their chokehold role: Patients may die, but shareholders are rewarded

Well, when there are only three of you in the richest market and you make a product that is literally not optional for people that need it, keeping that happy status quo is a pretty nice deal. But just how profitable is selling expensive insulin?

To give you a sense, let’s drop in on a study published in the open-source journal BMJ Health. To quote: “the study estimated the cost of production for a vial of human insulin is between $2.28 and $3.42, while the production cost for a vial of most analog insulins is between $3.69 and $6.16.” The price charged? Depending on who you ask and where you are, it varies, but the answer is a lot more than that. This chart from a 2018 Rand Corporation study is indicative:

Indeed, a recent (2020) paper looking into the matter found that the three dominant companies producing insulin derived “vast profits” from their sales. And where did those profits go? To shareholders in the firms. Share repurchases and dividends to company shareholders between 2009 to 2018 totaled some $122 billion. As the author points out, more funds are going to shareholders than to basic R&D.

Rosie Collington, the researcher, puts some numbers around this. “What we discovered was that as the list price of insulin has increased in the past decade, the ratio of spending on R&D relative to what the companies distributed to shareholders had actually decreased. While over the period of 10 years, the companies spent $131 billion directly on R&D, crucially we found that during the same period, the companies had distributed $122 billion to shareholders in the form of cash dividends and share buybacks.” In May of 2021, Lilly announced a further $5 Billion buyback program.

Not a good look when people are literally dying because they can’t afford these prices.

An increasing bipartisan consensus that the way things are is unacceptable

As with hearing aids, making insulin affordable is the kind of issue that can bring together stakeholders across special interest and party lines. With hearing aids, conservatives liked the deregulatory, free-market aspect of the over-the-counter change, and liberals liked the social benefits. With insulin, it’s possible to imagine similar cooperation among key stakeholders.

A role in the insulin pricing situation is clearly played by the large Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBM’s) who have a strange structure of perverse incentives, in that they benefit from higher list prices for pharmaceutical products with negotiated rebates for the manufacturers and agreements with insurance companies. They are attracting bipartisan criticism for their role in increasing drug prices in the United States.

More on them in an article to come – but check out the story of Todd Bisping and how he quietly took them on. I wrote about it in “Seeing Around Corners.”

The American Medical Association has weighed in, urging the Federal Trade Commission and the Justice Department (notably, not the Food and Drug Administration) to step in to help lower the prices for insulin. To quote: “It is shocking and unconscionable that our patients struggle to secure a basic medicine like insulin,” said AMA Board Member William A. McDade, M.D., PhD. “The federal government needs to step in and help make sure patients aren’t being exploited with exorbitant costs.”

Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi/Aventis are facing a class-action lawsuit over an accusation that they raised their prices in concert, in a way that is anti-competitive.

A variety of actors are calling for the reform of the system that protects patents through “evergreening” – extending the life of a patent not through breakthrough innovation (the original idea) but through incremental changes to the basic science. The Minnesota Attorney General, Lori Swanson, has sued the three dominant producers for price gouging.

Very sad stories

Unfortunately, there are way too many stories of patients who have suffered severe and debilitating illnesses when they can’t get the drugs to treat their conditions.

An inflection point?

It looks as though an inflection point for the current insulin business model may be underway. On July 28, the FDA approved an interchangeable biosimilar drug, Semglee. More importantly, a fourth company, Viatrus, will begin to compete in the U.S. insulin market. While the competitive effects are still going to be subject to negotiations among policymakers, PBM’s and the original manufacturers, the presence of potential competition is likely to at least moderate the most aggressive pricing maneuvers.

An even more substantial inflection point may be new developments that make insulin unnecessary for patients with Type 2 diabetes, who constitute 90% of the market. In 2019, the FDA approved oral tablets for the treatment of Type 2 diabetes.

Other efforts to treat diabetes range from cell editing, variations on immunotherapy, and even robotic implants. While they may end up displacing the need for insulin eventually, such therapies are often wildly expensive and are likely to be controversial as governments weigh the benefits.

What can we conclude?

As I’ve often said, when an organization has hostages, not customers, the seeds for an inflection point exist. Let the right mix of customer dissatisfaction, stakeholder alienation and shifts in concepts of how an organization can legitimately operate emerge and a formerly attractive business model can reach its expiration date.

Watch this space. Next up, potentially, PBM’s.

New skills for the new year?

While we’re on the subject of customers and strategic inflection points, you might be interested in investing in your own skill development. I’ve created two on-line, self-paced courses, one on discovery driven planning and one on creating customer insights that are up and running right now. They’re designed to deliver content you can use right away, with videos, explainers, downloadable materials and other goodies. Check them out at this link.