A board and governance level issue that doesn’t get nearly enough attention is whether firms are being run as value creators or value extractors. As economist William Lazonick points out, absent real pushback, it is all too easy for management to simply extract value from companies – value that was built up patiently, sometimes over years, by innovators. This is very bad news for our society as we shall see.

Financialization and value extraction in capitalist economies

The economist William Baumol attributed the spectacular growth of human flourishing in late-stage capitalism to what he calls the ‘free market innovation machine’ in which firms engage in an “arms race” to create the next innovation and stay ahead of others. This pushes everybody to do the very uncomfortable act of retiring the old and investing in the new.

It stands to reason then that performance in the long run has to do with making strategic decisions that allow a firm to continuously innovate. While this sounds obvious, there are very real tensions around the strategic decision to be innovative, most significantly about who shares in the in the value created by a successful innovating organization. This is reflected today in the decades-long debate over the distribution of resources between various stakeholders in a corporation – the shareholders, of course, but also employees, communities and others. For several decades, policy has tilted toward shareholders first, everybody else after or not at all.

William Lazonick is one of the most outspoken critics of this shareholder-first mindset. Since the Securities and Exchange Commission permitted open-market share repurchases in 1982, a concatenation of incentives have led to many management teams (and the boards who don’t stand in their way) engaging in what Lazonick calls the “legalized looting” of the American public corporation. He has a new book, Investing in Innovation: Confronting Predatory Value Extraction in the U.S. Corporation (currently available for free pdf download). In a previous book that doesn’t exactly pull its punches (Predatory Value Extraction), Lazonick criticizes the shift in management from a “retain and reinvest” approach to strategy to an “extract and exploit” approach.

It may well be that we are finally at a point at which we need to reconceptualize what strategic performance really is and how we measure it. If we go all the way back to Edith Penrose and her studies of the theory of the growth of the firm, she argued that investments in growth should be financed by retained earnings, with shareholders deserving to earn a fair return, but not more than that.

The Theory of the Growth of the Firm – a warning

As she says, (From the Theory of the Growth of the Firm Penrose p. xii) “Profits were treated as a necessary condition of expansion – or growth – and growth, therefore, was a chief reason for the interest of managers in profits. Moreover, the more profits that could be retained in the firm the better, for retained earnings are a relatively cheap source of finance; management had no desire to pay out to shareholders more dividends than were necessary to keep the capital market happy.”

She also sounded an early warning against allowing management teams to enrich themselves and their shareholders by unfettered extraction of value. In the 1995 introduction to a revised version of the Theory of the Growth of the Firm, she observes (Penrose p. xi) “I was not impressed by the reasoning behind, nor the evidence to support, the assumption that the managers or directors of large corporations in the modern economy saw themselves in business largely for the benefit of shareholders. After all, in the 1950’s the phenomenon of the firm run by the type of owner-managers who were not committed to the firm was not as evident as it seems to be today; it seemed to be a reasonable assumption at the time, it is now, some 40 years later, clearly inadequate. The role of financial institutions as shareholders can now be seen to require much careful analysis, as does the role of directors in their financial managerial functions who, as Lazonick has so clearly shown, may well be more interested in their own financial rake-offs through high salaries, stock options, golden handcuffs, bonuses, etc. than in the growth of their firms.”

A company that is imbalanced in where its resources go is weak and not resilient. Moreover, an excessive extraction of resources can leave a firm completely debilitated when conditions change and investment in the new is necessary. Kraft-Heinz’s write offs of brand value multiple times over would be a poster child here, as observers describe its brands as “withering.”

How much value extraction is too much

The numbers are pretty staggering. Citing Lazonick again, “The main instrument of predatory value extraction is the open-market repurchase of the corporation’s own outstanding shares—aka stock buybacks—the overwhelming purpose of which is to manipulate the corporation’s stock price. In 2012-2021, the 474 corporations included in the S&P 500 Index in January 2022 that were listed throughout the decade funneled $5.7 trillion into the stock market as buybacks, equal to 55% of their combined net income, and paid $4.2 trillion to shareholders as dividends, another 41% of net income.”

The evidence is compelling that firms that go overboard on compensating executive teams and shareholders put their futures at risk. Nonetheless, under pressure from investors, it’s all too easy for CEO’s to acquiesce to the lure of buybacks. It’s important to remember that unlike dividends, which return gains to those who hold shares (presumably because they have long term faith in the organization), buybacks only reward those who sell their shares, presumably because they either don’t believe the company has a strong future or because they can capitalize on a nice short-term bump in the share price.

Indeed, Pfizer’s CEO suspended its buyback program specifically in order to fund investment in its pharmaceutical R&D portfolio in the midst of the pandemic. On his third time around as CEO of Starbucks, founder Howard Schultz suspended the buyback program in order to invest in employees and other upgrades. Boeing was disgraced by accusations that its focus on financial performance had undercut its commitment to safety in the awful 737Max debacle.

This spills over into other sectors as well, those we count on to keep us safe and healthy. As Lazonick observes, pharmaceutical companies argue that they need high prices to invest in R&D, but actually, “the $747 billion that the pharmaceutical companies distributed to shareholders/sharesellers was 13% greater than the $660 billion that these corporations expended on research & development over the decade. In doing massive buybacks, the pharmaceutical companies undermine their own argument that they need high drug prices to fund innovation, even as they repeat this contention in opposition to drug-price regulation mandated by the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022.”

Reimagining balanced capitalism that works for the majority of people – ending the ‘wealth pump’

Harvard’s Rebecca Henderson has argued that we desperately need to reimagine capitalism, and suggests that the statistics on really long run shareholder return show that there is a strong relationship between running a firm with a balanced focus on operations and innovation and eventual total shareholder returns. Her book Reimagining Capitalism in a World on Fire is full of great suggestions. You can watch our Fireside conversation here, in which she pulls no punches. Capitalism is “committing slow suicide.”

For markets to work, she points out, we need counterbalances to the forces that reward powerful individuals to the exclusion of everybody else. We need strong government, strong civil societies and a voice for everyone involved in the process of value creation – employees, for example. For example, anyone right now can just throw greenhouse gases out the window without concern for the social cost, which is considerable. Right now, the easiest way to make money is to simply rewrite the rules in your favor as a business, which has resulted in the financialization of many of the world’s most advanced economies.

The consequence is that money that could go into improving wages and living standards for everyone races to the very top of the income distribution. Peter Turchin has eloquently warned about this, making the point that “general well-being (that is, of the overwhelming majority of population) tends to move in the opposite direction from inequality: when inequality grows, well-being declines, and vice versa.”

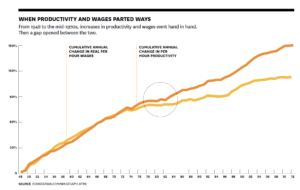

As he further points out, “what happened in the United States, which I studied very carefully, is that the governing elites essentially dismantled the New Deal. They reduced the power of workers to organize and bargain with employers. The minimum wage stopped growing and they, of course, reduced the taxes on themselves. And so this is what turned the wealth pump on and everybody probably saw this famous graph, where you look at the American worker productivity, which keeps growing after the 1970s, but the compensation stays flat or even declines. So the difference between compensation and productivity, that’s the wealth pump, that’s the mechanisms that pumped wealth from the poor, from the workers to the economic elites.”

Source: Profits without Prosperity

He studies societies in history that have experienced extreme inequality and excessive rewards to the elite, and how those societies have rebalanced their economies. It isn’t easy. As he notes, in the majority of cases, perhaps 80 or 90%, something fairly horrible happens. That might be a civil war, a transformative revolution or the collapse of the state. And so, in the 10 or 15% of good outcomes, it is always a concerted action by the prosocial segments of elites persuading the rest of the elites that we either impose reforms from the top, or you’ll have a revolution from below.” That is what happened in the United States during both the Progressive and New Deal eras. Now, many “elites” are begging the G20 to enact equalizing taxes on the wealthy.

So, a revolution from below, or reforms from above?

It certainly casts our current political situation in a fresh light. To close with an observation from Rebecca Henderson, “Real change happens in small rooms and in small actions that accumulate over time; there is plenty of capitalism to reimagine. You just have to raise your hand.”