My last “Thought Spark” was published before the dreadful implosion of the Titan submersible. Then, I was talking about intelligent failures. This time around, let’s focus on what my colleague Amy Edmondson would call a preventable complex failure.

“There hasn’t been an injury in the commercial sub industry in over 35 years,” he said. “It’s obscenely safe because they have all these regulations. But it also hasn’t innovated or grown — because they have all these regulations.” Stockton Rush, CEO of OceanGate.

That was from a 2019 interview which characterized Rush as a “daredevil inventor.” And perhaps that’s where the problems begin.

Three kinds of failures and why this one has lessons for us all

In her brilliant forthcoming book, “Right Kind of Wrong,” Amy Edmondson discusses three kinds of failures. There are the potentially intelligent ones. Those teach us things in the midst of genuine uncertainty, when you can’t know the answer before you experiment. There are the basic ones, that we wish we never experienced and which would be great to get a ‘do over’ on. And then, there is a class of failure that the doomed Titan submersible falls into – the preventable complex systems failure.

As she explained to the New York Times some years back, “Complex failures occur when we have good knowledge about what needs to be done. We have processes and protocols, but a combination of internal and external factors come together in a way to produce a failure outcome.”

Hubris, Failing to heed warnings, and more

Amy and her colleagues have written about organizations which managed to overlook or underplay “ambiguous” warnings that bad things were underfoot. To counteract such threats, organizations need to be able to envision a negative outcome, prepare as teams to take coordinated action and be open to receiving information that such a negative experience might be unfolding.

But the Titan? Here, the threat wasn’t even ambiguous.

Rush, the adventurous CEO behind OceanGate, the Titan’s owner, was an impatient man who saw regulations as barriers to innovation. In a heated exchange with Rob McCallum, an industry veteran, he wrote “I have grown tired of industry players who try to use a safety argument to stop innovation and new entrants from entering their small, existing market…. We have heard the baseless cries of “you are going to kill someone” way too often. I take this as a serious personal insult.” McCallum responded, not pulling any punches, by saying “I think you are potentially placing yourself and your clients in a dangerous dynamic. Ironically, in your race to Titanic, you are mirroring that famous catch cry “she is unsinkable.” Having dived the Titanic and having stood in a coroner’s court as a technical expert, it would be remiss of me not to bring this to your attention.”

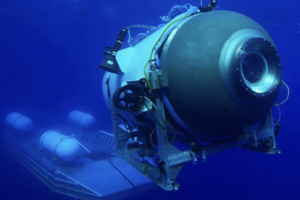

The ship used an unconventional design, relying on carbon-fiber materials to create a cylindrical tube, rather than the sphere-shape most submersibles utilize. The cylinder meant that water pressure would be unevenly distributed. The carbon-fiber construction, in contrast to more conventional metals, was prone to weakening under the wear and tear of repeated excursions, unlike most designs that use metal, commonly steel.

In 2018, the closest thing to a regulatory body that the submersibles business has, the Marine Technology Society, wrote a scathing letter to Rush. As they said, “Our apprehension is that the current experimental approach adopted by OceanGate could result in negative outcomes (from minor to catastrophic) that would have serious consequences for everyone in the industry.”

But regulators were not the only ones to become alarmed. In a classic example of failing to ensure safety in complex operating environments, those who voiced concerns were not only silenced, but dismissed. Two employees – well, technically now former employees – of the company behind the doomed vessel expressed concerns about its design. David Lochridge, the company’s former director of marine operations, claimed in a court filing he was wrongfully terminated in 2018 for raising concerns about the safety and testing of the Titan.

Acknowledging small failures before they become big ones…

While ignoring the warnings from what Andy Grove might have called “helpful Cassandras” is bad enough, Rush also violated one of the cardinal rules of preventing large-scale complex systems failures. This is to recognize and account for small-scale failures before they build up to become large ones. And by all accounts, the troubled Titan submersible experienced plenty of smaller failures before the one that was ultimately catastrophic.

The first submersible created by the company didn’t survive testing and was scrapped.

The bit of news that got Lochridge fired was the realization that the viewport that allowed passengers to see out of the vehicle was only certified for depths of up to 1,300 meters. To get to the level of the Titanic, a craft would need to be able to go to 4,000 meters. Listen to the messenger? Not exactly. “OceanGate gave Lochridge approximately 10 minutes to immediately clear out his desk and exit the premises,” his lawyers alleged.

Another submersible expert, Karl Stanley, reported on unnerving knocking noises coming from the ship, later saying “What we heard, in my opinion … sounded like a flaw/defect in one area being acted on by the tremendous pressures and being crushed/damaged.. From the intensity of the sounds, the fact that they never totally stopped at depth, and the fact that there were sounds at about 300 feet that indicated a relaxing of stored energy/would indicate that there is an area of the hull that is breaking down/ getting spongy.”

A person who did manage to pay for and ride in the submersible to visit the Titanic remains now calls himself “naïve” for taking the risk. As he reflects on the experience, he calls it a “suicide mission.”

Josh Gates, host of the Discovery show “Expedition: Unknown” had concerns that led him to take a pass on a voyage on the Titan. As he recalled, “We had issues with thruster control. We had issues with the computers aboard, we had issues with communications. I just felt as though the sub needed more time, and it needed more testing, frankly.”

Normal accidents, failure and high reliability organizations

Charles Perrow, in an insightful 1984 book Normal Accidents: Living with High Risk Technologies, pointed out that unless they are very carefully designed, complex systems will be failure prone because they interact in ways people find difficult to anticipate. Since the publication of that book, we’ve learned a tremendous amount about operating complex systems safely.

Note how the Titan case seemed to fly in the face of these operating considerations.

- A preoccupation with failures – especially small ones – that might cascade into larger ones. This includes prompt reporting and investigation of what went wrong.

- Deep understanding of causality. Rather than oversimplifying cause and effect in a complex system, participants probe deeply into how factors are connected.

- Constant monitoring of the state of things and strong situational awareness on the part of operators.

- Investment in redundancy and slack resources – this contributes to resilience in the event that things do go wrong.

- Expertise rather than hierarchy – resilient, high reliability systems put decision rights with those who can best solve the problem, not with those who occupy a given hierarchical rank.

It isn’t that one can’t explore innovative approaches to unfamiliar areas. But, as deep-sea explorer and director of the movie Titanic James Cameron observes, “If you’re an explorer… there’s this idea that there’s a certain level of risk that’s acceptable. I actually don’t believe that. I think you can engineer against risk. I think you can minimize the risk down to the few things that you can’t anticipate.”

Perhaps that is the right kind of wrong, indeed.