It’s fun to reflect on how my course “Leading Strategic Growth and Change” has evolved over the years. I first took over as the Faculty Director for the course in 1998. Everyone was abuzz about this new thing we called “the Internet.” Venture capitalists had uncapped free-flowing pens, MBA students were talking about becoming entrepreneurs and it seemed that we were on the brink of a whole new age. It turned out that we were, just not in the way we expected. Way back then, the late Max Boisot was miles ahead of just about everyone in identifying the nature of digital goods and what that meant for organizations strategically.

A front row seat to the revolution

Max Boisot was a brilliant scholar and theorist who was among the first to recognize that the advent of the digital revolution was not just about another whizzy technology but a fundamental shift in the logic of value creation. He argued that the industrial revolution involved harnessing non-renewable energy sources to produce industrial goods. The Information Revolution, whose outlines were only becoming dimly understood in the late 90’s, involves substituting information for energy to produce knowledge-intensive goods.

He opened his class with this brain teaser:

In 1978 a student at Oxford University decided to improve his chances of academic success by borrowing a copy of his final examination questions. Not content with punishing him for cheating, the university prosecuted him for theft. The judge threw the charges out. The university, he pointed out, still had the questions. The student had not kept the piece of paper on which they were written. He had merely copied it. Because deprivation is the essence of theft, the student had not stolen anything.

(Source: The Economist, May 4th, 1991. p.21)

As the class discussion proceeded, what participants began to explore was exactly in what ways information goods were different than physical ones, with significant implications for the creation, growth and eventual loss of competitive advantages. Among Max’s most important arguments was that simply possessing information was insufficient to develop an advantage – what matters more is how it moves throughout your organization. As competitive advantages become shorter, the pace at which a company can move to build new advantages becomes a competitive differentiator, and yet very few firms have a strategically consistent way of understanding knowledge flows.

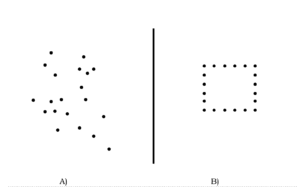

He would then offer the class a challenge: Imagine that they were using one of those old-fashioned international telephones with scratchy sound that required a physical operator. Which of the following figures would be easier to explain to the person on the other end so that they could replicate it, say in another country (no snapping pictures on your smartphone allowed!

Choice “B”, of course would be a lot easier to convey then the random pattern represented by Choice A. And this gets to a fundamental element of information goods – they need to be given structure in order to convey meaning and all information goods exist to do is convey some kind of meaning.

The “I-Space” or information space

Max Boisot’s Information Space (I-Space) Framework offers a powerful lens for understanding how organizations can architect information flows. The framework maps information along three critical dimensions: codification (how structured the information is), abstraction (how conceptual versus concrete), and diffusion (how widely shared). Together, these create a three-dimensional space where different types of knowledge live and move.

Consider for instance, the difference between the knowledge possessed by a Buddhist monk and a bond trader, one of Max’s favorite comparisons. The monk might well spend years studying, learning and deeply embodying the traditions of his group. The knowledge he possessed would be idiosyncratic to that specific time and place. Bond traders, on the other hand, operate with highly codified knowledge about, say, prices, that travels around the world in an instant. Everyone who knows bond trading has access to exactly the same information at all times.

Here’s the issue, however. The information possessed by the Buddhist monk is full of richness and deep meaning. The information the bond trader uses is very abstract – it has been extremely well codified and everybody knows what the codes mean, but it has been stripped of nuance and meaning. That’s what codification entails. Codification also enables diffusion to take place. When a piece of information is only in a person’s head, other people don’t have it. When it’s codified – by say, writing this newsletter – now it can be widely shared and even those who aren’t present or didn’t personally know the author can share the information.

Organizations that can take uncodified, undiffused information and give it shape and meaning by fast learning can outpace slower competitors by the way knowledge is architected. Consider why Tesla maintained its electric vehicle lead for so long. It wasn’t just superior battery technology. Tesla excelled at moving knowledge through the I-Space more effectively than traditional automakers. They rapidly codified manufacturing innovations, abstracted lessons across product lines, and diffused insights throughout the organization. Meanwhile, legacy automakers had knowledge trapped in silos, poorly codified, and moving through bureaucratic layers at glacial speed.

The Four Strategic Zones

The I-Space is a conceptual model with four distinct zones where knowledge operates, each with different strategic implications.

Zone 1: Tacit Knowledge (Low codification, high abstraction, low diffusion) This is where breakthrough innovations often begin—in the minds of individuals or small teams. Strategic implication: You need different management approaches here. Traditional project management kills innovation in this zone. Instead, create protected spaces. There needs to be time to tinker. Funding should be allocated on a funding basis, not a budget basis. A great resource for understanding knowledge of this kind is Safi Bahcall’s wonderful book Loonshots.

Zone 2: Proprietary Knowledge (High codification, moderate abstraction, low diffusion) This is historically where many knowledge-intensive companies built protections and barriers that kept others out of their territory. Patents on pharmaceuticals, trade secrets, and the like limit others’ ability to copy what you can do. It’s knowledge that’s structured, but not widely shared. Here’s the problem: Back in the day when such knowledge was combined with physical assets, say a Nylon plant for DuPont or a razor factory for Gillette, there were entry barriers that could keep others out of the space. With digital products, the physical “moat” goes away, making this zone much harder to defend.

Zone 3: Public Knowledge (High codification, high abstraction, high diffusion) This becomes commoditized quickly. You’re not going to create a strategy that is differentiated in this zone because everyone has access to the same information. Information that was once tacit, moreover, as competition and imitation kick in often ends up in this space. One of the major impacts of the current generation of artificial intelligence platforms is potentially to turn what was once hard-to-create proprietary knowledge, such as how to code, into public knowledge with the aid of AI. We are already seeing fascinating stories of how this is playing out, with uncertain consequences for those who spent years in some cases building up once-scarce, now common, expertise.

Zone 4: Common Practice (High codification, low abstraction, high diffusion) These are industry standards and best practices. This kind of knowledge is just table stakes for you to participate in a sector – You must excel here to play, but excellence here won’t differentiate you.

The Movement Imperative

The real strategic insight behind all this is that knowledge doesn’t sit still in the I-Space. It moves. And the companies that master this movement outperform those that don’t.

Amazon’s AWS success illustrates this. The company took tacit knowledge about managing massive computing infrastructure, including the need to completely refactor their systems which few other companies had ever done (Zone 1). After having codified the knowledge behind AWS for their own use, they had the idea that other companies might benefit from this secure, cloud-based, flexible information architecture. They created reusable services (Zone 2). Then, they selectively diffused it to customers while keeping core architectural insights proprietary. They orchestrated knowledge movement to create a platform that competitors struggle to replicate.

The Execution Challenge

The I-Space Framework isn’t just analytical—it’s actionable. But execution requires rethinking how you manage knowledge flows. Most organizations optimize for knowledge sharing (diffusion) without considering the strategic implications of what they’re sharing and when. Further, in many typical bureaucracies what Max called “blockers” are often allowed to run rampant – political interests, incentives and other personal motivations can get in the way of the free flow of knowledge development that forms the center of information goods.

Smart companies create “knowledge portfolios” where different types of information are managed according to their I-Space position. They accelerate movement when it creates advantage and slow it when it protects advantage.

The Competitive Reality

In an era where information moves faster than ever, understanding how knowledge flows are moving across your organization isn’t optional—it’s essential for strategic survival. Companies that treat all knowledge the same way, or that optimize for transparency without considering competitive implications, will find their advantages eroding faster than they can build new ones. The question isn’t whether your knowledge will move through the I-Space. It will. The question is whether you’ll orchestrate that movement strategically or let it happen to you.