This article was co-developed with Alex van Putten, Partner at Cameron and Associates, and draws from our 2017 article “How to Set More Realistic Growth Targets.”

It’s always easy to project rosy growth goals that will happen in some misty future. The trouble is that you need to be making hard decisions today about appropriately resourcing those growth ambitions.

OK, strategists, let’s talk about growth gaps. A growth gap is the difference between what your base business and any new business you might be developing will deliver, and what your strategic ambitions are. This rather charming explainer video from our buddies at Innosight lays it out. Most organizations are thunderingly bad at taking the kind of action that would not leave them with a growth gap.

We are perennially unrealistic about the future

There are a lot of reasons. The planning fallacy, a concept proposed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in 1979, suggests that people always under-estimate the time and the cost it will take to do just about anything. Few executives have the discipline to realistically evaluate their sources of growth. And very few organizations, in our experience, have a disciplined way of managing their portfolios of investments. So what happens is that projects that are vaguely assumed to be able to deliver future growth are under-staffed (or not staffed at all) while zombie projects that everybody knows are going nowhere get to lumber along, sucking up talent and resources along the way.

Let’s take the example of one large company Alex and I worked with in 2017. It’s executives agreed that it needed $250 million in new revenue from innovative new products in five years. Beautiful spreadsheets were crafted and many high-energy “ideation boot camps” were held. Don’t even get me started on “innovation theater”…

But…

Mapping expected growth to the opportunity portfolio

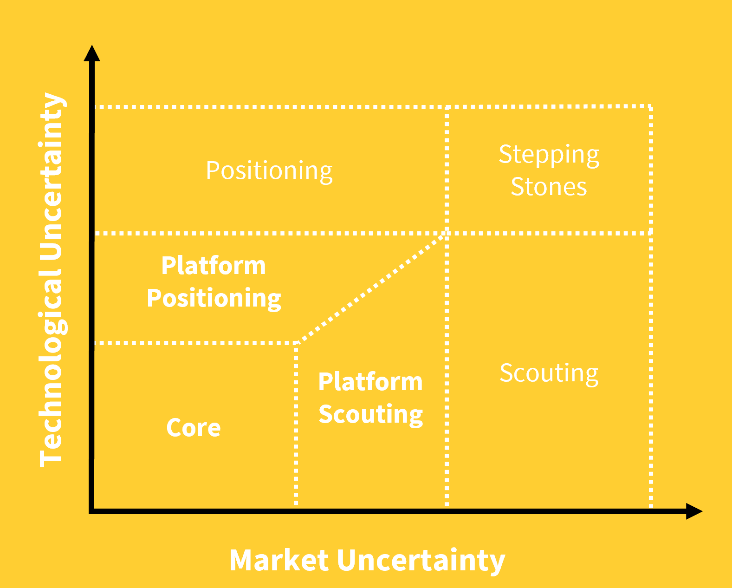

We started mapping those future projections to the resource commitments the company was making using a framework called the Opportunity Portfolio.

Using this framework, projects are evaluated with respect to their market and technical uncertainty, their resource-intensity and their upside potential. Where uncertainty is the highest, these are best managed as options for future growth – interesting ideas that give you the right to make future investments, with potentially large returns, but given the uncertainty they represent, are highly likely not to work out. Nonetheless, these are options for future growth.

Platform Launches are candidates to join your core business – ventures like Amazon Web Services opening up an entirely new vector of growth for the company. In the early days, these generate revenue, but not a lot of profits given the need to invest in them to get them established. And of course, investments in the core business keep the wheels turning on the business of today.

The company in this example did not want the innovation team to consider growth from the core, because this was viewed as incremental.

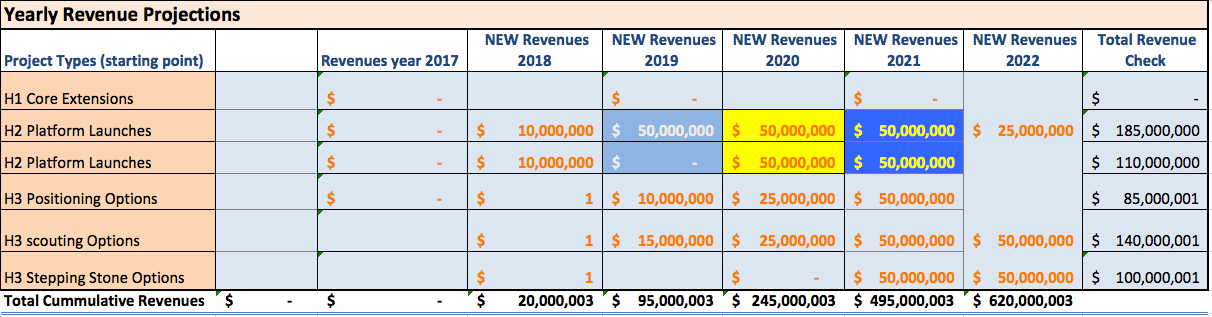

Projecting new revenues to the five areas in the Opportunity Portfolio was relatively easy. As the following table shows, it led to a comforting view of the future growth potential of the current portfolio.

Each block in the table denoted new revenue that year resulting in cumulative new revenue that can be found at the bottom of each column. Note that the table implicitly projects limited investment and a slow start to the new growth initiatives, with no new revenues in 2017, modest new revenues in 2018 and significant new revenues really only beginning in 2020 and 2021.

The table offers an attractive view of the firm’s growth prospects, with a projected total of $620 million in new revenues by the 2022 timeframe.

Beware comforting – and unrealistic – spreadsheets

And this is where spreadsheets – which a colleague of ours dubs ‘quantifications of fantasy’- can lead to unrealistic conclusions. The big problem is that spreadsheets tend to reduce the world to linear models, when the growth process, in reality, is non-linear.

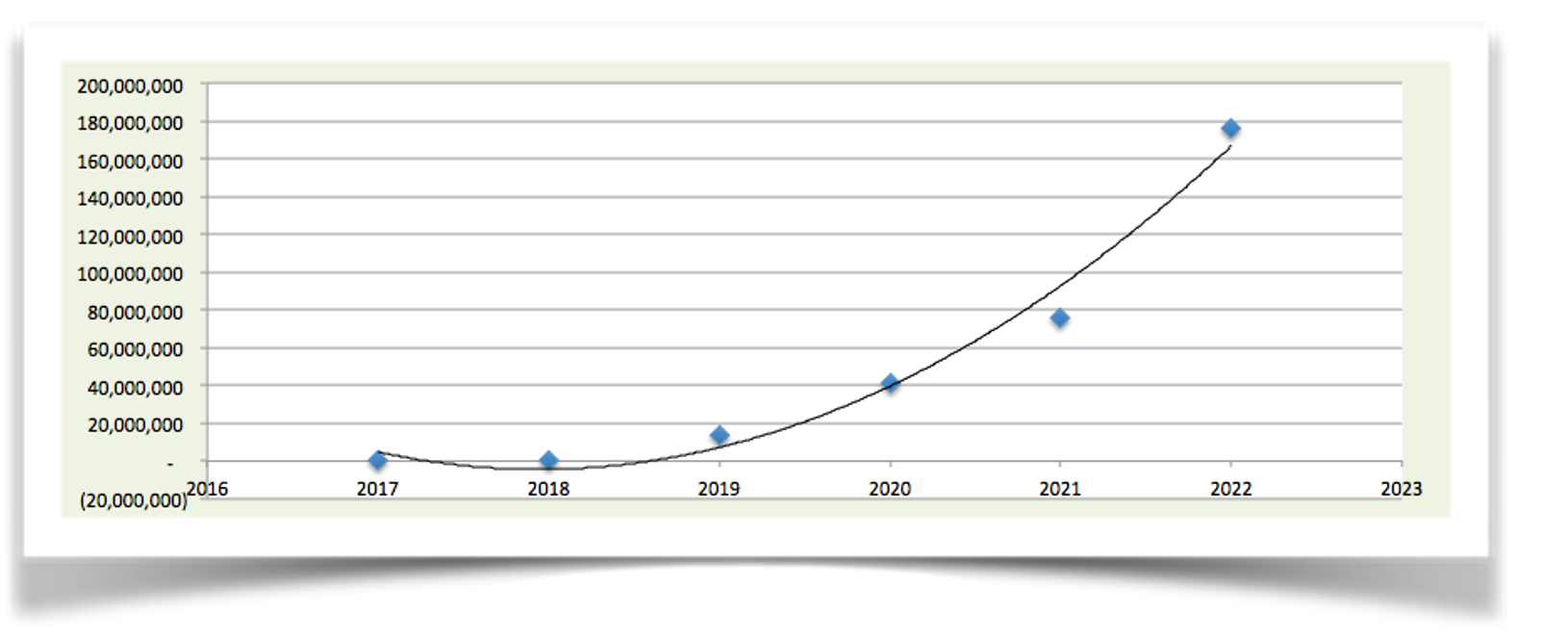

Imposing just a bit of realistic discipline with respect to the likely times at which revenues will be realized led to a very different conclusion about when the growth program would show results

With the growth initiative just getting underway in 2017, the company’s own projections showed that significant new revenues would not be realized until 2020, representing a three-year lag between initiating their growth projects and reaping the rewards from them. Of particular concern on our part was how long it would take for each project to achieve 50% of its target revenue for each year, testing the assumption of linear growth embedded in the projections.

To do this, we modeled the assumptions in the plan with a technique that incorporates non-linear growth functions, a logistic growth model. It uses three inputs: the revenue goal for each year of the model, the assumed first year revenue, and the inflection point, or time that they thought would be required to reach 50% of the revenue goal.

This allowed us to create the following chart, based on projections in the plan documents, for the likely trajectory of their revenue growth plans, given the assumptions they provided to us about the inflection point of achieving 50% of their revenue targets.

This analysis revealed that attractive looking cumulative revenue numbers in the plan did not take into account the dynamics of timing. Even though the table projected cumulative new revenues from the plan of $620 million, a dynamic view that takes timing into account, shows that at best the new revenue is likely to be in the $180 million range – a far cry from the target.

Projects that only got started after 2019 would be of little help in hitting the portfolio target revenue in 2022, because they simply do not have the time needed to begin to deliver results. This in turn called into question the planned strategy for resource deployment. Maximum resources would be needed early on, with an eye towards really driving growth in 2017 and 2018.

The dilemma of acceleration and timing

New ventures developed internally go through three major stages. The first is the idea stage, when everybody’s baby is lovely, there are no constraints and all ideas are terrific. Ideation, in well organized innovation programs, eventually becomes incubation, in which ideas get to face the hard, cold reality of whether they could ever become viable businesses. Ironically, success at incubation creates the next set of issues, in the phase we call acceleration.

You can think of acceleration as helping your tiny little venture, which is sort of on the “on ramp” of your business as gaining the speed and momentum to join everybody else. You need to bring in the lawyers. You need to pay off organizational and technical debt. But the most critical thing of all is that you need to provide sufficient resources that you set your venture up for success. All too often, what happens in reality is that decision-makers flinch.

Rather than putting the money, talent and focus behind getting those new ventures into the marketplace, executives under-invest, usually due to the pressures of maintaining cash flows in the existing business. The result? Slow takeoff, or none at all, failing to give the new venture a realistic chance.

The firm we’ve been examining could easily have been on track to hit the $250 million target by 2024. Unfortunately for them, the goal was set to get there by 2022. You can guess what would have been likely to happen. Heads would roll, the people making the projections would be criticized or worse, and (most ironically and unfairly of all), the people who simply happened to be in management roles by the time the innovation investments came to fruition would get the credit!

Implications

- Mind the gap! Do you even understand what your growth gap is? The process is actually not that complex – simply look at the growth trends of your existing lines of business and compare them to where you think your strategy needs to be at some point in the future. Usually, there will be a gap.

- What portfolio of projects might help you fill it? Some combination of acquisitions and organic growth are probably attractive. When time is tight, you’ll place more emphasis on acquisitions. If you have time, organic growth makes more sense.

- Third, get away from linear thinking about how your growth initiatives will unfold. All living things, businesses included, have a non-linear pattern to their growth. Tools such as the logistic model can help you be more realistic about what you can achieve within a given timeframe.

- Finally, don’t allow your assumptions to become facts in your own mind. The growth journey is about learning, discovery and finding a business model.

If you’d like to learn more about the tools we are building at Valize to manage portfolios, please reach out to growth@valize.com.