In the heady days of coming up with what you think is a breakthrough idea, it’s easy to get carried away by assumptions. Forcing yourself to create a deliverables specification can create powerful discipline.

Entrepreneurs often occupy what Alberto Savoia calls “thoughtland.” This is that delightful time in the development of a business where we’re just talking, there’s no such thing as a bad idea and everybody’s baby is beautiful. Market research in Thoughtland is lots of enthusiastic conversations.

Here’s the problem – you’re never going to build an actual business if you stay in Thoughtland. You have to figure out what needs to be true in the real world for an actual new business to be created. I’ll leave the concept of pretotyping (which is brilliant) to Alberto. What I’m going to focus on here is once you have an idea that you think might work, how you plan it in a way that is grounded in reality. It involves a document I call the deliverables specification that spells out what is technically and operationally required to make a dream into reality.

Selecting a business model and required revenue

Although it is often skipped over, one of the first choices you’re going to have to make in launching a new business is that of the business model. While there are a lot of complex ways of talking about business models, I like to focus on just two elements: the unit of business (what you are selling) and the deliverable specifications (how you go about creating and selling it).

Let’s illustrate with a simple unit of business – a product. I’m going to use the Tego Roll and Go as our example. The Roll and Go is a re-imagining of the toolbox (now raising funding on Kickstarter). The idea is to break down conventional carrying solutions into modular, configurable sections that can be zipped together in any format the user desires, to carry whatever they need.

To take a discovery driven approach to a project like that, you’d start with the customer job-to-be-done, which is to take stuff that doesn’t fit nicely in a conventional toolkit from point “A” to point “B”. Next, you’d think through what you (as an entrepreneur) would have to get out of this when sales are fully developed. I have no idea what Parker Thomas, the founder, has in mind, but let’s say he’d be happy clearing $100,000 annually from the invention.

Notice, we’re starting with profits first. Then we work backward into what revenue would be required to produce these profits (this is also called a reverse income statement).

Operating fairly knowledge-free here, we’d have to make some guesses about return on sales when the business is fully operational. Let’s look at Tumi for inspiration. That company has struggled mightily with the slowdown of travel during the pandemic, but in its better years (2010 to 2015) averaged 17.8 % profit margin, so let’s call it 20% to keep it simple (by the way these numbers are wrong and that’s OK).

If we work with a 20% profit margin for Thomas, that suggests the business will have to produce revenue when it is all grown up of about $500,000. The product comes initially with a set of 7 different sections, and the Kickstarter campaign has “priced” a set at $69. That means to make those numbers, Tego would have to sell 7,246 units or thereabouts 7-piece units in a typical year. Is this reasonable?

Well, as of this writing, the project has raised $42,280 from Kickstarter investors, with 313 folks buying the 7-section product at $69, 116 buying two at $129, 16 buying four at $249 and three die-hard supporters going for it and pledging $489 for an 8-unit set. And all this for product that doesn’t exist yet! A few hundred customers will have to translate into a few thousand if this dream is to be realized.

The next step is to create a deliverables specification, which outlines what must be true to bring this business model to life.

The deliverables specification – First Model

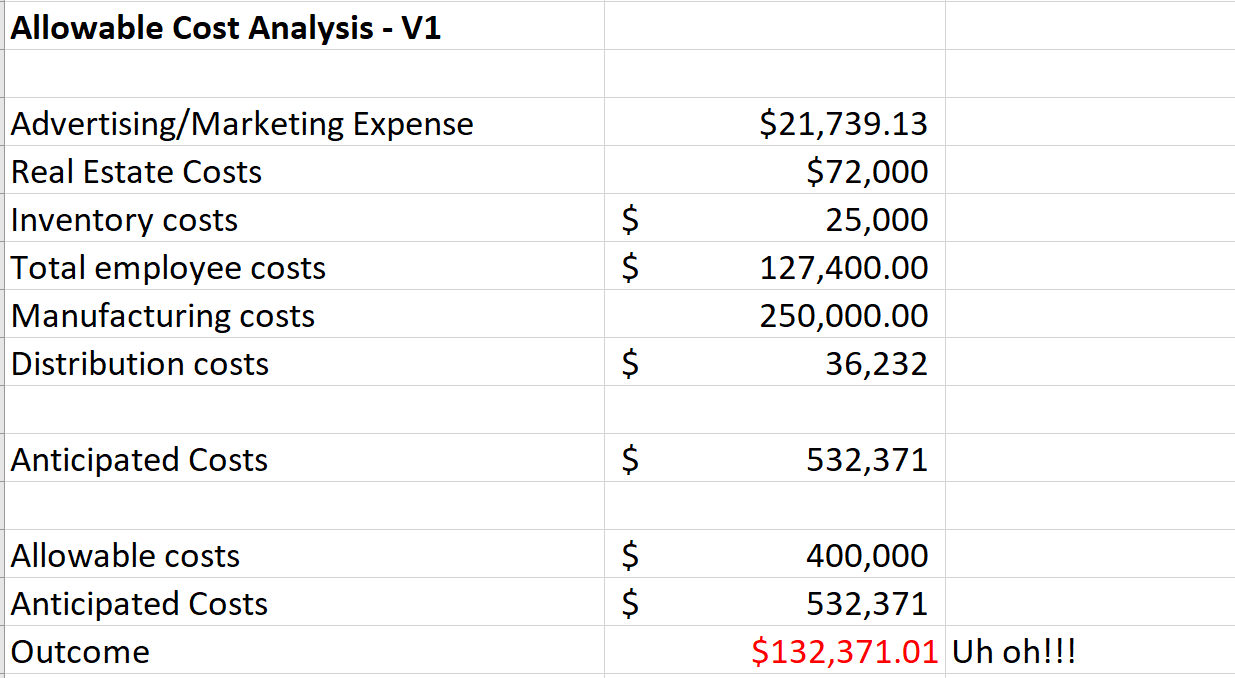

The first important number in a deliverables specification is what I call “allowable costs.” In this case, that would be the $500,000 required revenues less the before-tax profit that would be required for our entrepreneur / inventor of $100,000, giving us a permitted spend of about $400,000.

Now we turn to the guts of the business and how we might calculate some of the “what would need to be true” for the business. If we just take some typical small business expenses, we’d want to make assumptions for factors such as advertising expense, real estate expenses, inventory, manufacturing costs, costs for staff and costs for distribution. An easy way to play around with these numbers is to put them in relative terms – for example, for the initial model I built for Tego, I figured (assumed) that it would have to spend $3 in advertising/marketing for every unit it sold.

The first model I developed for the business made these assumptions:

- Advertising and marketing expense – $3/sale

- Facilities required of 4,000 square feet at a rental cost per year of $18/sq foot

- Inventory cost as a percent of sales of 5%

- Required employees: 2

- Manufacturing cost as a percent of price of 50%

- Distribution cost per item of $5 each

Then what you do is an allowable cost analysis, which looks like this:

Yikes! If the initial assumptions I made are anywhere close to accurate, this business is not only going to fail to make our entrepreneurs’ dreams come true, it’s actually going to lose money!

This is the wonderful thing about creating a deliverables specification, particularly before you’ve gone and blown a whole lot of investment capital. Those numbers won’t work for us to meet our goals. And this is totally normal with a discovery-driven plan – what you want to be able to do is figure out what doesn’t work in order to figure out what does.

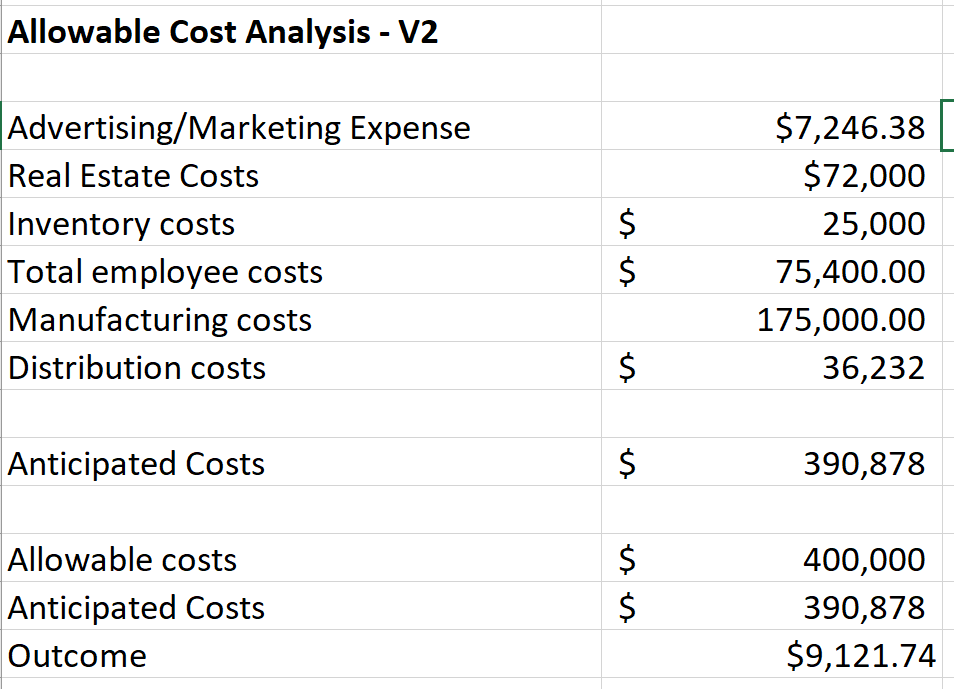

Back to the drawing board – deliverables specification, version 2

So, back to the spreadsheet. What might we be able to change?

Well, let’s say we could be so clever about advertising and marketing that we can get that number from $3/sale to just $1. That might be because we are social media superstars, because we already have a devoted following, because we have one of the most popular groups on Facebook, you name it. Here’s the point – your team is now able to discuss the reality of how you’re going to get the word out rather than making grand assumptions.

The company did make a super-cool video to highlight the product! Have a look – it really gets the message across.

Real estate is trickier – much as it would be cost-effective, you hardly want an assembly and distribution center operating out of your bedroom. So let’s leave that one for now. Same with inventory – with today’s shredded global supply chains (and the fact that the product is manufactured in Vietnam) you don’t want to be caught short with too little inventory on hand. So we’ll leave that one as well.

People cost? Maybe we can figure out some smart way to need just one person, not two. That could be because of smart work redesign or other business model tweaks, but that could free up some cost there (by the way, I prefer not to think of people as a cost – if I were doing this for real, I’d add in a calculation for how many extra sales a well-trained employee might contribute, but we’ll leave that complexity out for now).

What about manufacturing cost? Let’s talk to our chief engineers and see if there’s anything they could do to get the manufacturing cost to 35% rather than 50% of our final price.

Distribution? Likely to remain about the $5 mark unless the Post Office or UPS decide that we deserve a subsidy – unlikely.

So we tweak the model and what do we find?

Well, this is better – a lot better. We’ve gone into the black, even after making space for Parker Thomas to get his $100,000 required profits out of the business. It’s still a thin profit margin, but a workable one given these assumptions.

Planning to Learn and Focus

This example illustrates the power of applying a discovery driven discipline to building out the plan for a business. As we’ve seen, it makes the critical assumptions explicit. It provides constraints and concrete goals that have to be met. And it does all that without costing very much at the outset.

Thinking of launching something new? Give it a try. And let me know how you made out!

Checkpoint Learning System

This material, plus downloads, video explainers and the spreadsheets that go with are going to be part of an online learning system geared around key discovery driven checkpoints that will launch in September. There will be 6 modules that cover critical customer insight aspects of the discovery driven growth approach in the first iteration.

For early customer pricing or to test-drive a sample module, please contact growth@valize.com and one of the team will get back to you with details.