Although the early warning signs that an inflection point is on the way are often detectable years, even decades, in advance, trying to time most inflection points is incredibly frustrating. Not so with demographics. In this month’s newsletter, I’ll explore the implications of a potential baby bust and see what else might be lurking around this particular corner.

Although the early warning signs that an inflection point is on the way are often detectable years, even decades, in advance, trying to time most inflection points is incredibly frustrating. Not so with demographics. In this month’s newsletter, I’ll explore the implications of a potential baby bust and see what else might be lurking around this particular corner.

The overnight tipping points that have been building up for years

As my colleague Amy Webb noted in our really fun fireside chat (see around counter 11:37), the first patent for a flying car was filed in 1917, and every year since then, we’ve seen flurries of patents on that same idea – the flying car, some of which were actually built and flew – for a bit, at least. So too with many other trends. It look a lot longer than even Reed Hastings of Netflix expected for the world to finally convert to streaming platforms for the consumption of video. It took decades for genuine picture-phones to take up residence in our pockets, even though a 1953 prediction proved surprisingly prescient. And we’re still in the early stages of robot servants that might free us from domestic chores.

Demographics are a great exception to this rule of unpredictability. After all, every single 20-year-old of the year 2030 exists right now, today, and they are all ten. So for someone trying to take a peek into the future, demographics offers one of the few variables that have a teeny bit of absolute predictability to them. The one I’m going to focus on this month is one that has some observers concerned, and that is the increasing likelihood of a so-called ‘baby bust’ in which an entire demographic cohort is born in far fewer numbers than one might anticipate.

The tricky calculus of parenting in a pandemic

Let’s bring in the pandemic and human responses to it. In the early stages, as the seriousness of the deadly novel coronavirus were being grasped, the imagery was very much of a temporary interruption to normal life. It would be gone by April, with warmer weather. Hopes for a July disappearance were sadly, dashed. Well, perhaps it would be contained enough for schools and universities to re-open in the fall – and unfortunately that happened unevenly and in fits and starts. Coupled with this unprecedented amount of uncertainty and a total lack of clarity about whether supporting institutions might re-open, families, often with both parents working full-time, are grappling with a child care crisis of unprecedented proportions. Essential workers are cobbling together solutions to allow them to show up at work and keep their children safe, few of them optimal.

Women, particularly, are under tremendous pressure. Whether they are well off or less so, women are disproportionately bearing the brunt of household responsibilities. For professional women seeking to stake an equal claim on professional jobs with their male peers, family responsibilities have become a major drain – as one apocalyptic headline put it, a “disaster for feminism” as family forms return to their 2-parent-1-breadwinner form of decades ago. Women with young children at home are picking up the majority of child care and home maintenance tasks, and in many cases, giving up on the prospect of working outside the home entirely for as long as child care is risky or unreliable.

For those that don’t yet have children, or who are considering having more, the disincentives for childbearing are formidable. Unsurprisingly, the Guttmacher Institute’s research suggests that a whole lot of women are reconsidering when – or even whether – to have children. As a recent story in Time Magazine tells us, Shelby Parker, a middle school teacher in Ohio, has decided not to have a second child at the moment in light of pandemic-related anxieties. She isn’t happy about it, but it doesn’t feel safe to proceed – as she says “I’m grieving for the family I thought I would have.” The same article points out that in the United States, having a child is closely associated with the real risk of falling into poverty.

For many women, of course, seriously thinking about having children follows on another practice that is being thoroughly disrupted by the pandemic – namely, weddings. A $74 billion industry in past times, everybody from catering halls to hotels to florists to dressmakers flourished from the annual ritual of couples saying “I do.” Enter the era of COVID-19, and that is all on hold for a good many couples.

Even women trying to conceive are up against obstacles. Regular doctors’ offices – where, for instance, a woman might need to go to have a long-lasting IUD removed – are closed, or available only for crises. Fertility clinics are closed. And lest we think these numbers don’t matter, a Center for Disease Control report identified over 81,000 babies who were born with the assistance of assisted reproductive technology.

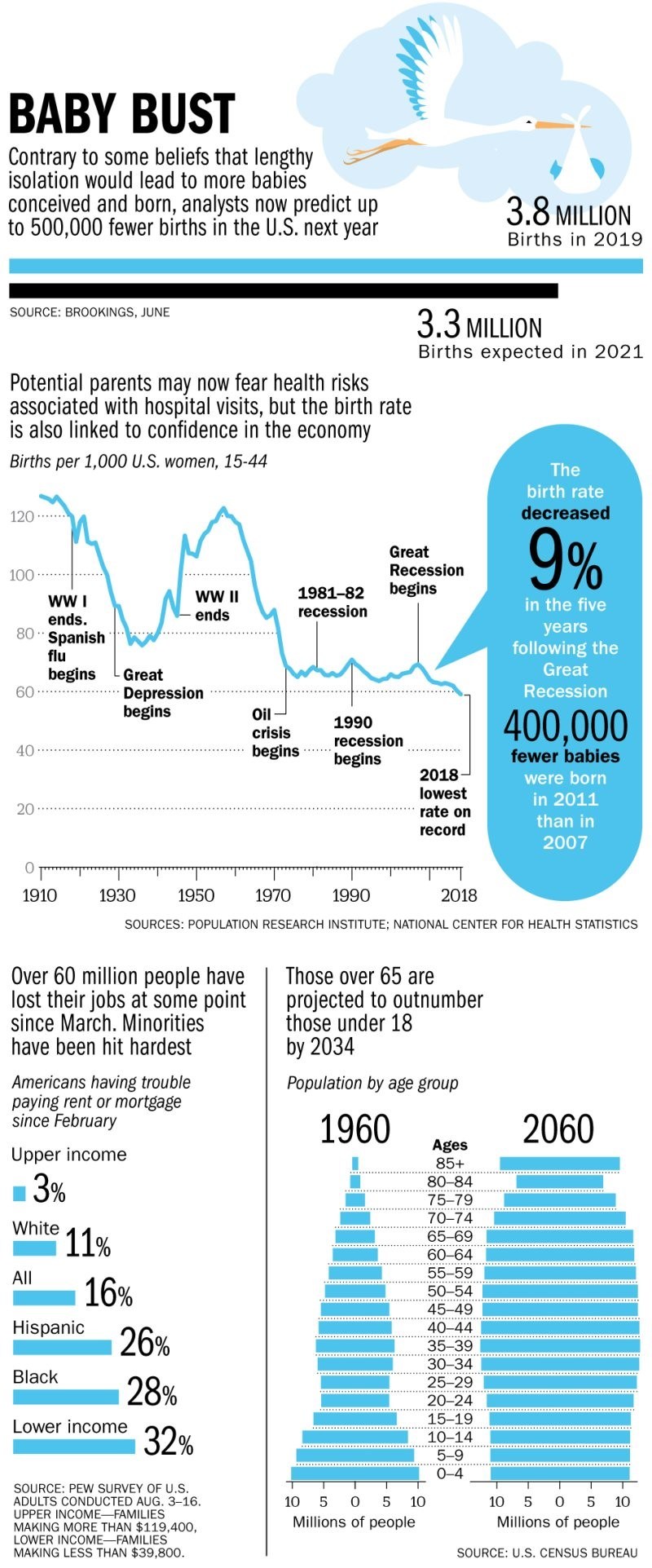

In short, we may well be on track to experience a historic “baby bust.”

What does a baby bust look like?

Rahul Gupta, the Chief Medical and Health officer for the March of Dimes puts it almost poetically. “In the United States alone, at least 1 million children who would have been born over the next three years will never giggle, take their first steps or grow up to contribute to the great American experiment.”

Even as fewer babies are being born, relatively speaking, older adults are living longer. The result is a predictable aging of most of the populations of the developed Western world. There will be more people who are dependent on fewer people of working age. There will be more demand for health-care services, even as we have a health care system that is focused much more on disease management than on health care. And of course, if you’re in the business of selling products aimed at babies and young families, a relatively sudden decrease in demand could prove catastrophic.

Low fertility rates among Western democracies, and particularly in the United States are nothing new, despite hand-wringing over the consequences of COVID-19. Indeed, the country has been facing a “demographic cliff” since at least the onset of the Great Recession of the latter 00’s. Lots of punditry has examined how shrinking populations are a bad thing. Doubters suggest that rates of innovation and development will suffer. Any income increases for younger people are likely to be gobbled up by the need to care for older ones. Stagnation, not growth, becomes the norm in their world. That may well be so (remember, we shouldn’t be confusing predictions with preferences). But, perhaps we can put our optimists’ hats on and explore a few ways in which there might be unexpected benefits to smaller families and fewer people.

Some potential positives?

So let’s say that we do have a baby bust, followed by a continuing trend of lower fertility levels. There might be some positives here (for those people lucky enough to be born, that is).

Smaller Families. Fewer babies imply smaller families. And smaller families, especially in poorer places, are associated with a plethora of positive consequences. Children from smaller families, which are also likely to have siblings spaced further apart, live longer. They are less likely to catch debilitating diseases. They get a bigger slice of their parents’ attention and resources. Mothers in such families are less likely to die in childbirth or suffer long-term effects of pregnancy-related problems. Indeed, a Johns Hopkins study found that children from smaller families (defined as 4 children or fewer) could look forward to a life expectancy a full three years longer than children from larger families in similar places. Since life expectancy reflects a mix of health, economic and social goods, that suggests that for each individual member, smaller families have benefits. This extends to siblings as well – a 2016 study found lifelong negative impacts on older children when younger ones were added to the family mix.

The Environment. Fewer humans imply less environmental stress. The pandemic has, to some extent, been an experiment in exactly the kind of carbon reduction that environmentalists argue is essential to address global warming and the extreme weather events (among other calamitous outcomes) it generates. Nonetheless, scientists warn, we risk slipping back into bad habits without more fundamental rethinking of the resources we use, per person. Fewer people, plus sensible public policy, could make environmental goals easier to achieve. And some the new habits we’ve acquired – turning roads into places to eat, using bicycles more, figuring out how to be safe and entertained at home – might stick.

Housing. Fewer people imply that things that are currently in short supply might become more accessible. Some economists have suggested that the price of housing, for instance, rose as the ‘baby boom’ generations sought to settle down, and that with the advent of declining birth-rates, house prices may well decline. Others have noted that the large homes in which boomers raised their families are holding, or even dropping in price as that generation downsizes, ironically putting them in competition with younger generations for the smaller starter homes with which new home-buyers typically start. But if the laws of supply and demand hold, fewer people should mean less demand and more supply. And of course, if those in construction have fewer customers, they will have to cater to those that are around.

Education. On top of pandemic-related issues stressing the current model of higher education with unknown outcomes, fewer potential students obviously will put many institutions at great risk. While some will doubtlessly close, others will apply innovation to the task. Admissions to most institutions, for starters, will be less competitive. Pricing will start to become more sustainable (it will have to). Education is unlikely to be confined to the traditional 18-22 year old ages, but spread across generational cohorts. And, good news for many is that we may finally break the back of rampant degree inflation (which I’ve written about before). Forward thinking employers such as Google and Tesla are looking for employees to demonstrate that they have necessary skills, degree optional.

Jobs. Fewer workers imply more competition for their talents. This could be one of the most significant positive effects. With fewer workers, organizations will have incentives to be better employers. If you can’t count on simply hiring people with the skills you need on open markets, there will be a much stronger incentive to recruit, develop and retain valued people.

This in turn implies that employers may need to entertain raising wages and otherwise creating good jobs. My colleague, Zeynep Ton, has advocated for this for years. She is beginning to be able to measure good jobs approaches with the tools provided by the Good Jobs Institute. Corporate involvement in creating good jobs will likely take a different form than that documented by Rick Wartzman’s interesting book The End of Loyalty: The Rise and Fall of Good Jobs in America. But the intuition of the corporate leaders he profiles remains relevant. He cites Charles Kettering, a General Motors Vice President, laying out the case for what is widely regarded as the philosophy behind the United States’ postwar economic boom. “In the future, a major corporation must accept as a moral obligation the task of propagating new industries. It must pay more and more attention not alone to the improvement of old things but to the development of new things” (p. 13).

Social Contract? The effects on the global economy wrought by forgetting these lessons has been devastating, as is now revealed in the coronavirus crisis. Wrapped in an ideology made both popular and politically acceptable by economists such as Milton Friedman, we’ve witnessed half a century of increasing income inequality, downward pressure on wages, slowing fundamental innovation, and the dominance of economically optimized, but brittle, supply chains for just about everything. These in turn have enabled economic financialization and the dominance of firms, such as private equity firms in corporate decision-making. From a human and community perspective, the results of their focus on economic profits rather than long-term organization and community viability have been catastrophic for many.

An inflection point we can actually track

In Seeing Around Corners I point out the importance of looking at leading indicators which are often fuzzy and difficult to measure. Demography generally, and birthrate specifically, is an exception. We can measure how many babies will be born in 2021, and from there pretty accurately gauge when those babies will be at significant turning points in their lives. The question I would leave you all with is this – are you paying attention?