The unsolicited attempt by video rental chain Blockbuster to take over electronics retailer Circuit City looks like a pretty desperate move. In short, a company that prospered with the rise of the whole rent-it-out couch potato ethos that began to flourish in the 1980’s, hasn’t been willing or able to renew its core business, even as its advantages were eroding under pressure from competitors with different business models (such as Netflix), buying DVD’s and greater availability of alternatives, such as movie downloads and video on demand from cable companies.

Blockbuster’s CEO (who came out of retirement to turn the firm around after doing a good turnaround job at 7-Eleven) feels that cost savings and efficiencies will make the aggressive, indeed, bet-the-company move successful. Interestingly, at least at this stage, there doesn’t seem to be any compelling new business model in the offing. Circuit City stores would likely offer videos and games for rent (woo hoo – now there’s a big innovation) and Blockbuster stores might be able to sell hardware such as portable media players (ditto). He seems to think that the movie rental and consumer electronics businesses are ‘converging’ and cites the Apple stores as a case in point, even going to far as to note that Apple’s stores could be a model for the post-merger Circuit City/Blockbuster bid.

I’m not one to ever say ‘never’ but this one has me scratching my head.

I’m not one to ever say ‘never’ but this one has me scratching my head.

Missing: Clearly defined customer segment with clearly defined needs

For starters, where is the market segment with a compelling need that this combined company will address? Apple stores are not just stores—they are complete retail experiences that showcase truly breakthrough products in a dramatically different way than competitors. Wal-Mart’s segment doesn’t value experiences so much as good value, so that is differentiating for them. Best Buy has been brilliant at customer segmentation and has gone so far (with its acquisition of the Geek Squad and the emphasis on product knowledge among its ‘blue shirted’ employees) as to make the retailing-purchasing-installing-using experiences far superior to those at other retailers. There doesn’t seem to be much customer focus here.

Assumption of ‘convergence’ or denial of reality?

A recent Wall Street Journal article notes that CEO Keyes believes that convergence between video consumption and consumer electronics is underway and that the merger will facilitate the postioning of the combined company to benefit. Convergence? Hardly. What’s happening here is that the core of Blockbuster’s business—movie rentals—has been in decline for some time and is likely to simply erode as a source of future profits and growth. Sure, there will be some customers who continue to use the service—just as for decades after deregulation meant you could purchase phones there were customers still renting them from Ma Bell—but if investors and other stakeholders are looking for growth, clinging to an increasingly obsolete core is not the answer.

Not being smart or disciplined about managing a full growth portfolio

The Blockbuster saga, to me, is a repeat of what happens to many a successful company over time. With the growth and success of the core business, more and more focus is placed there. It’s all too easy to keep pumping investment and people resources into that business. Financial tools and other conventional management practices make investments anywhere else look unattractive. When conditions change, competitors copy or leapfrog and customers’ desires shift, a company that has over-invested in the core can find itself with few choices. The next step is usually a desperate one—typically, the company will be acquired by another firm, often not for its declining core business, but for its other assets – such as brand, talent, or intellectual property. Sometimes the lure is simply assets such as real estate! The Blockbuster approach of Circuit City is simply this same process with a twist, the twist being that the CEO presiding over the declining-model company will be the one designing the strategy for revival (hmmm…).

The upshot: Invest in growth options before you need them!

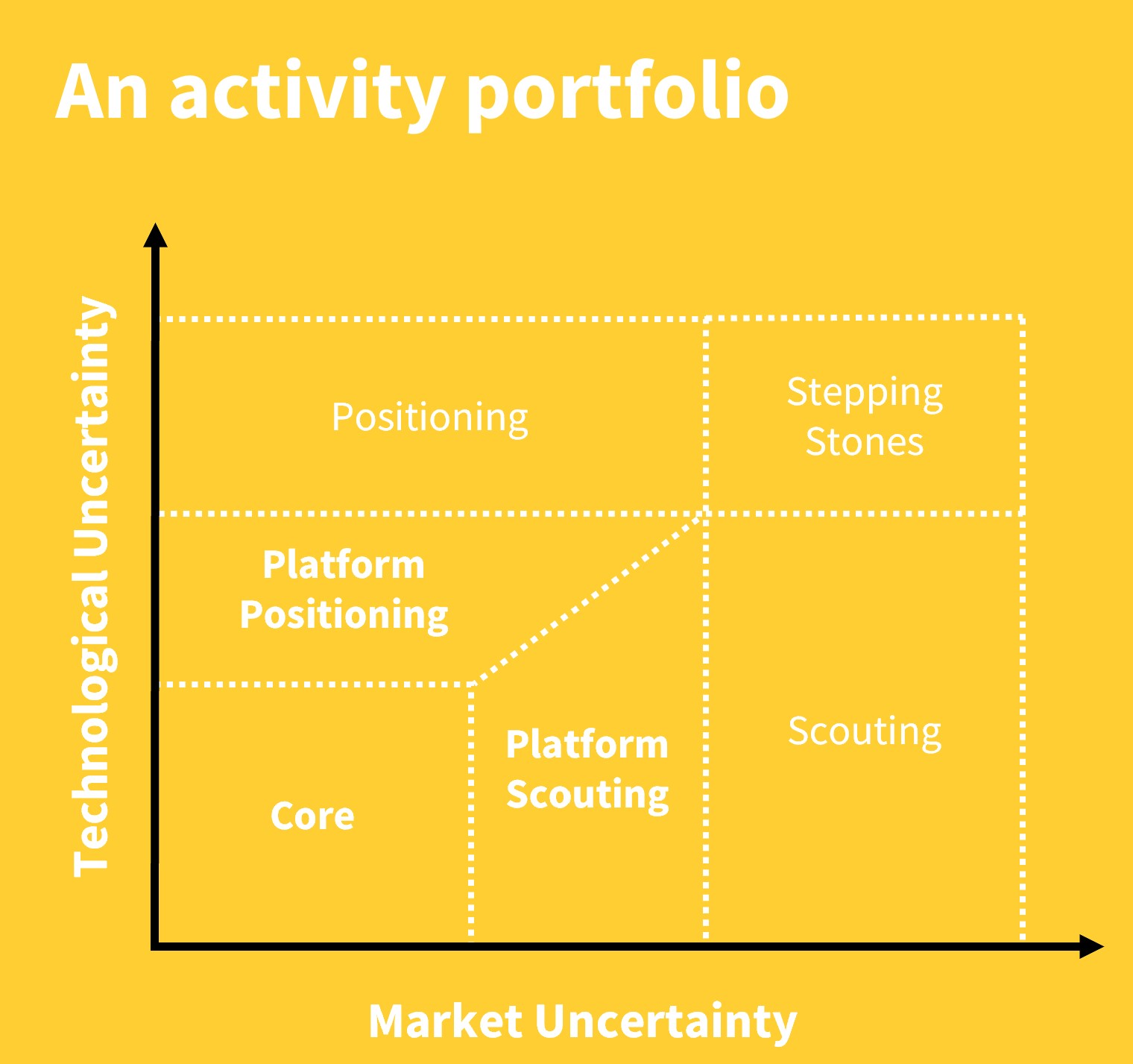

What should the good folks over there at Blockbuster have done differently? Well, if there is trouble in the core business, the obvious answer is that you have to discover or find adjacent businesses to renew or create a new core. How do companies do this? I’ve argued that they need to think about investing in portfolios of opportunities. The chart gives an illustration.

If you think of your investments as distributed across dimensions of uncertainty, with market uncertainty extending across the bottom of the graph and technical or capability uncertainty going vertically to the left of the graphic, you have a way of picturing the activities you are investing in. Each boxes’ worth of activities serve different strategic purposes.

- Core enhancements are clearly those things you do to keep the current core business healthy. That’s essential, as without a healthy core you don’t have a lot of other options (as the Blockbuster scenario makes all too clear)

- Platform launches are next-generation businesses – you can think of them as candidates to form a new core business

- Options, just as the name suggests, are small investments you make today that give you the right but not the obligation to make a bigger investment going forward

My guess is that Blockbuster (and Circuit City, which isn’t in great shape itself) under-invested in the options that could have been crucial to the discovery of a new business model. Now, it’s trying the risky and difficult route of putting its core business into discovery mode – a practice that is likely to lead to expensive disappointments rather than the small, contained-downside, experiments that options represent.