During times of change, especially when the change is threatening, the right response for leaders is to double-down on flexibility and problem-solving. Unfortunately, as researchers have discovered, CEO’s often fall victim to the “threat rigidity” effect. Under pressure, their utilization of information narrows, they revert to controlling behavior and they generally rely on things that used to work.

Lyft Share price

Bad symbolism and worse – what’s up with some of these CEO realities?

As I wrote about last week, a number of stories have surfaced about CEO’s having, let’s just say, less than stellar moments when faced with stress. Here’s another one – David Risher, the newly installed CEO at Lyft, facing pressure from an improved driver experience at Uber and other issues, issued a blank order for everybody to get back in the office, Pronto!

My colleague Bob Sutton suggests that to understand this, we can go back to some ground-breaking research on what has come to be called the “threat-rigidity” response. The main idea is when individuals, groups, and organizations are under threat, they narrow their focus of attention, fall back on habits from the past, and simplify in a way that doesn’t take account of the true challenge. This is also often associated with the inability to deal with complexity and concentration of power among top dogs.

As he says, “this narrowing and associated rigidity, they argued, is often maladaptive, because, during times of change, when being flexible and innovative is most adaptive, people, teams, and organizations are prone to freak out and freeze up.”

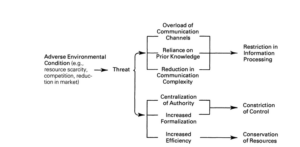

I was intrigued and went back to the original 1981 article that introduced the concept to the world, written, as Bob says, “by the brilliant Barry Staw and two of his then PHD students Lance Sandelands and Jane Dutton in @ASQJournal. Lance and Jane later got married!” Here’s a telling graphic, and let’s just use the Lyft example to illustrate – there’s some kind of issue in the market (Lyft stock is now $9, down from its peak of around $80). There’s a sense of urgent crisis, of things that have changed. As a leader, what does this mean?

An understandable response to a big threat

Well, for starters, you are going to have everybody coming at you. Employees, (especially those surviving a layoff) are facing negative emotions and are looking to you to paint a hopeful picture for the future. Shareholders want to know the plan. Your leadership team is apt to be facing similar pressures. Politics can get out of hand. Reporters bug you with nasty questions. And on and on it goes. It’s only natural that facing the onslaught of communications you tend to fall back on what you know (which may not be relevant to the current situation) and try to shut down as much of the noise as possible (which can create blind spots). That in turn means the information available to you is restricted to what you think you can absorb.

At the same time, given a desperate need to feel you are in “control,” there is often a tendency to centralize authority and make it more formal (“everybody back in the office”) and push for known ways of improving performance in the here-and-now (cutting back on training or innovation, pushing for greater efficiency, pulling the levers that have always worked before). See this article for the consequences of this for your innovation function.

What I hadn’t appreciated until going back to the original piece was how much of this is both known and not new. As the authors observe, “The Penn Central Railroad, for example, continued paying dividends until cash flow dried up completely; Chrysler Corporation, when faced with the oil crisis and rising gasoline prices, continued large (but efficient) production runs on its largest and most fuel-inefficient cars until inventories overflowed; the Saturday Evening Post continued to raise its prices as circulation dropped.” The same applies to people – when we feel a threat, we revert to what worked before, whether or not it makes any sense in the current situation (exhibit A: Antonio Perez at Kodak pushing the company into what ended up being a disastrous focus on printing.)

Threats have their uses – mobilizing resources

Now this sounds bad, and it can be. But other streams of social science research suggest that sometimes the only way to free up critical resources is to articulate a threat – a call to action, a need to change. But you don’t want to wallow in the threat.

As Clark Gilbert’s research suggests, once you have the resources to address the challenge, it can be adaptive to reframe the threat as an opportunity, and allow parts of the organization to focus on that part of the equation, figuring out how the organization should respond, perhaps in a novel way. Note that you’ll have to offer some buffering between that piece of the organization and the ones manning the ramparts!

At a personal level – how do you avoid becoming toxic in a threat situation?

It’s worth repeating Bob’s advice here for those CEO’s who would like to avoid showing up in bad-boss-of-the-moment videos, taken from his book on surviving bad bosses.

- Beware of contagion. A lot of social science research shows us the power of social proof – we tend to regard as acceptable the behavior of those we think are our social peers. Rudeness, incivility and selfishness are actually contagious, like the common cold. So, before you get sucked into a situation which can bring out the worst in you, consider staying away. That could be physical distance, fewer contacts, or if the situation is really unbearable, quitting.

- Power tends to bring out bad behavior in all of us. Another robust research finding is that powerful people tend to exhibit less empathy, become more exploitative and worry a lot more about their own needs than that of others. So, figure out ways to counter those tendencies. As my partner, Ron Boire, (himself a former CEO at many name-brand companies) says, the lower in the hierarchy you go, the kinder you need to be.

- You’re not doing anybody favors with overwork. As Rob Cross and Karen Dillon point out in their terrific book The Microstress Effect, being overloaded with commitments, meetings, communications and just general excessive busy-ness can degrade the quality of your work and your life. Figure out what you can take off your plate to keep room available to be a reasonable human being.

- Genuine apologies make a difference. If you find yourself transgressing, a genuine apology goes a long way toward helping the situation and potentially teaching yourself some important lessons. Note – these are not non-apology apologies. Back to our “pity city” CEO who wrote “I feel terrible that my rallying cry seemed insensitive.” That’s not taking ownership – a real apology would reflect a genuine sense of remorse, not of being misunderstood. And, just sayin’, if you find you have to apologize a lot, maybe there is a deeper issue here.

- Setbacks are a good opportunity for introspection. As Pixar co-founder Ed Catmull reflected about working with Steve Jobs, “Jobs wandered in the wilderness for a decade. In the course of working through and understanding these failures, and then succeeding at Pixar, Jobs changed. He became more empathetic, a better listener, a better leader, a better partner. The more thoughtful and caring Steve Jobs was the one who created the incredibly successful Apple. Jobs remained a notoriously tough negotiator, a challenging person to argue with, and a perfectionist. But Catmull observes that Jobs’s greatest successes came only after he abandoned the notorious mistreatment of others that plagued his early years.

None of these leaders woke up wanting to be noticed for the wrong reasons. And I bet they have plenty of advice-givers all around. The dilemma is that often those advice and feedback givers are not offering the candid feedback that would be truly helpful. So, if you are in a position of managing other people, some introspection is well worth the time. Perhaps consider a little coaching now – before you end up as a bad example on the Twitterverse.