When your business model depends on profiting from your users’ ignorance, eventually the gig will be up. So it seems to be for Facebook, or Meta, which had a historically horrible day last week and began to lose significant numbers of users for the first time.

Illustration credit: The New York Times “Privacy is too big to understand.”

When I first proposed that Facebook could be facing a massive negative inflection point in my book Seeing Around Corners, my editor was nonplussed. It was mid-2018, and at that time it looked as though the company could do no wrong. It had by then succeeded in wiping out much of the traditional publishing business model, had successfully pivoted to mobile, gobbled up (together with Google) pretty much all digital advertising spending, acquired a stunning user base of over 2 billion people, made pivotal acquisitions of potential competitors (WhatsApp and Instagram) and was enjoying substantial user growth.

“You really think Facebook could get into trouble?” he asked me. Why, yes, I replied – the weak signals were already there.

Institutions and ecosystems lag reality

As I wrote in the book, social media “had a difficult 2018. It included the spread of ‘fake news’, false accounts, election and voter manipulation, the hijacking of online accounts, selling individuals’ most personal information to third parties, racial profiling, allowing the impersonation of celebrities, and targeting vulnerable populations.” And we were all to some extent scratching our heads at how we got to this juncture.

With any big inflection point, it takes time for the institutions and systems around it to absorb and adjust to its implications. For instance, when motion pictures first became a reality, nobody knew what a “movie” was. So the very first movies were basically filmed stage plays. As my future Friday Fireside Guest Frank Rose notes, “every time a major new medium has come along, it has taken people 25 or 30 years to figure out what to do with it. What you get in the interim is adaptations of old forms. Television was invented around 1925, but it was basically radio with pictures until the early 1950s, when comedy shows like I Love Lucy introduced the sitcom format—the first type of storytelling that’s native to TV.”

With any big inflection point, it takes time for the institutions and systems around it to absorb and adjust to its implications. For instance, when motion pictures first became a reality, nobody knew what a “movie” was. So the very first movies were basically filmed stage plays. As my future Friday Fireside Guest Frank Rose notes, “every time a major new medium has come along, it has taken people 25 or 30 years to figure out what to do with it. What you get in the interim is adaptations of old forms. Television was invented around 1925, but it was basically radio with pictures until the early 1950s, when comedy shows like I Love Lucy introduced the sitcom format—the first type of storytelling that’s native to TV.”

Gradually, then suddenly

A mistake many people make is thinking that just because a system has not reacted yet is that it never will. In 1879, for instance, Peter Collier, the Chief Chemist of the United States Department of Agriculture, investigated adulterated food products. The problem, he and his colleagues concluded, was more of honesty than production. As Collier said at the time “Where life and health are at stake no specious arguments should prevent the speedy punishment of those unscrupulous men who are willing, for the sake of gain, to endanger the health of unsuspecting purchasers.”

Then, as now, scientific conclusions weren’t sufficient to lead to change. Deeply entrenched manufacturers and providers resisted any effort to control how they operated. It took a change in public sentiment to eventually cause a large-scale social shift.

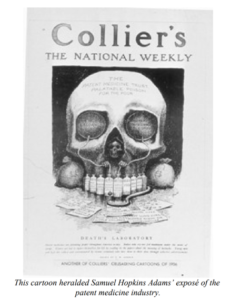

For instance, as a paper documenting the rise of food regulations points out, “Collier’s magazine ran a 10-part feature from October 1905 to February 1906 by Samuel Hopkins Adams. The series, entitled “The Great American Fraud,” excoriated the patent-medicine industry for strong arming, deceiving, addicting, poisoning, and killing the public with their outrageous cure alls for everything from babies’ teething to old age.” Upton Sinclair’s scathing book The Jungle, which documented the grisly conditions in Chicago’s meat-packing industry further struck a national chord. The result over the coming decades were hundreds of laws and regulations, backed up by new enforcement regimes involving on-site inspections of manufacturing plants.

A similar gradually-then-suddenly process took place over the long history of regulating smoking and tobacco use. Indeed, a CDC report on how the current regulatory regime, including the recognition that smoking harms health, included an astonishing catalog of tactics used by the tobacco industry to prevent the public from demanding legislative action. They include intimidation, alliances, front groups, campaign funding, lobbying, legislative action, buying expertise, philanthropy and advertising and PR. Facebook has used pretty much all of these tactics in its efforts to avoid regulatory interference with its business model.

The harms from spending time with Facebook products

It isn’t that the company does not know that using its products can be harmful. Not at all – Facebook conducted extensive research on the effects of its products (particularly Instagram) on users, specifically on teenage girls, finding pretty horrific negative mental health consequences. But, as a major expose in the Wall Street Journal reports, “Some Instagram researchers said it was challenging to get other colleagues to hear the gravity of their findings. Plus, “We’re standing directly between people and their bonuses,” one former researcher said.” The article clearly shows the company prioritizing its own financial well-being over the mental health of its users, much in the same way the snake oil purveyors of old did.

Which brings us to a poison-in-our-food kind of moment for Facebook. “It is clear that Facebook is incapable of holding itself accountable. The Wall Street Journal’s reporting reveals Facebook’s leadership to be focused on a growth-at-all-costs mindset that valued profits over the health and lives of children and teens,” Sens. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) and Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.) said in a joint statement.

One likely outcome, in my opinion, is that just as the government forced manufacturers to be allowed to provide access to food inspectors in their plants, companies such as Facebook are going to be forced to allow outsiders to examine the flows of data through their systems. Organizations such as Jim Steyer’s Common Sense Media are proposing exactly those remedies.

Unease with surveillance capitalism

Dangerous mental health effects aside, I pointed out in my book that many observers are expressing unease with what Shoshana Zuboff has called “surveillance capitalism.” She defines it thus:

I define surveillance capitalism as the unilateral claiming of private human experience as free raw material for translation into behavioral data. These data are then computed and packaged as prediction products and sold into behavioral futures markets — business customers with a commercial interest in knowing what we will do now, soon, and later… Right from the start at Google it was understood that users were unlikely to agree to this unilateral claiming of their experience and its translation into behavioral data. It was understood that these methods had to be undetectable. So from the start the logic reflected the social relations of the one-way mirror. They were able to see and to take — and to do this in a way that we could not contest because we had no way to know what was happening.

As Zuboff points out, there was a historical concatenation of forces that allowed the big social media companies to “get away with it.” A post-9/11 consensus that certain kinds of surveillance were in the public interest. An anti-regulatory mood among policy makers. Methodologies designed to keep us ignorant and accepting that this is inevitable. And most of all, no practical way of opting out.

To end this? Policies that are similar to those that ended the horrific Gilded Age practices of abusive workplaces and excessive concentrations of wealth, she would argue. The first is a “sea change in public opinion”. The second is new laws and regulatory systems that are fit for purpose for the post-inflection point social economics. The third is more fair playing fields for competition.

As Zuboff notes, “Every survey of internet users has shown that once people become aware of surveillance capitalists’ backstage practices, they reject them… we see a historic opportunity for an alliance of companies to found an alternative ecosystem — one that returns us to the earlier promise of the digital age as an era of empowerment and the democratization of knowledge.”

Facebook’s no good, very bad, horrible day

Which brings us to February 2 of 2022, and an earnings call of historic proportions. For the first time, Facebook’s total number of users has declined. It’s struggled to retain young users. Its expensive Metaverse bets look highly uncertain, with no clarity around the route to eventual profitability. Regulators are blocking its efforts to create financial products. TikTok is drawing eyeballs away from Meta’s core platforms and was the most downloaded app in the whole world in 2021.

But the biggest damage to Facebook’s operating model comes from exactly the behavior Zuboff described. When we have a choice not to participate in being a cog in the great surveillance machine, we choose to opt out. Apple made a change in its operating system in April of 2021 that accomplishes this by giving users the option of being tracked or declining. Given a choice, we collectively say “no way.” In fact, only 33% of users of iPhones and iPads agree to the tracking.

And the result for Facebook? An anticipated $10 billion or more in lost sales for 2022. While that’s not going to bankrupt the company any time soon, that’s a lot of revenue to go “poof” almost instantly. Investors? Not happy – they wiped about $200 billion off Facebook’s market cap overnight.

As the Washington Post’s Megan McArdle points out, Facebook is now facing the reality of being dependent on another ecosystem participant – in this case Apple.

Beyond Facebook – a larger inflection point?

R “Ray” Wang, in his wonderful book Everybody Wants to Rule the World offers a perspective on where all the digital giants, Facebook included, might be heading. See a replay of our Friday Fireside Chat here. He suggests that the decline of digital giants is likely to begin with an overwhelming backlash against them. It won’t be huge at first, of course, but “fissures” such as the choices made by Apple iPhone users, hearings in congress, and any number of calls to limit the power and reach of the big players are here, today. Eventually, immense pressure from the public will result in politicians responding with laws reining in these companies.

The ultimate destination of today’s digital giants, Wang speculates, may be that they will be subject to new institutions that will “ensure citizens will have the right to critical infrastructure as a public good.” In other words, they will be viewed and regulated as public utilities and the personal data they collect protected as a global human right to privacy.

In a way, Wang’s argument reflects to some extent Carlota Perez’s view on the long cycles of capitalist development. The capital flowing to investment in a new technology builds the infrastructure upon which the next is built. Viewed in this light, the coming inflection point for Facebook may be a useful development for us all.

The latest at Valize

Meanwhile, we’ve been busy at Valize developing the next version of our SparcHub software, which provides visibility into the management of your innovation and transformation processes. We’re also offering on-line learning modules which help you quickly get up to speed on the processes of discovery driven growth, strategy and customer insight. Individuals can purchase them by clicking here. For enterprise plans contact growth@valize.com and we’ll get you some options.