As we conclude this year’s holiday in honor of the life of Martin Luther King, Jr., many people are still wondering whether his dream of true equality between races will ever happen. My Friday Fireside conversation with Harvard’s Robert Livingston offers an optimistic approach.

Figuring out where to start

When I invited Dr. Livingston to join me by the fireside, he said he’d be happy to do that, but only under one condition: that I’d read his book The Conversation first. In approaching the book, he instructs readers to move through it the way it was written, beginning with the acknowledgement that structural racism even exists through stories about how to address it to actions that anyone can take.

As he points out, so often when he consults with organizations about how they can constructively improve their diversity, equality and inclusion initiatives, they want to jump straight to the solution, as in “just tell us what to do!”. As he points out, that is as silly as going to a doctor and saying “just prescribe me some pills.” Before we can even get to figuring out where to start, we need to diagnose the conditions first.

As he recalled, quoting Einstein, if given an hour to solve a pressing problem, he’d spend 55 minutes figuring out what the problem is and 5 minutes on the solution – “most people,” Livingston points out, “want to spend 5 minutes on the problem, and 55 minutes on doing something.”

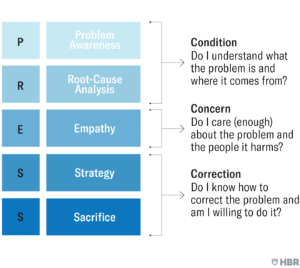

The approach he features in the book is organized around his PRESS model.

P: Problem awareness. Do you understand the real problem?

R: Root cause analysis. Do you understand why the problem was created?

E: Empathy. Do you care?

S: Strategy. Do you know what to do?

S: Sacrifice. Are you actually willing to take the necessary actions to implement the strategy?

A point he makes with great insight is that people aren’t just rational beings – we respond to other people, we respond to stories and we respond to narratives (as my future Friday Fireside guest, Frank Rose will help us to explore).

Structural racism hurts everybody

One of my favorite stories in the book has to do with a guy Livingston calls “Ted” – a White man from the middle of the country who grew up in a town with zero diversity. Ted ended up in his Harvard class by accident, due to a registration mishap. It turned out to be transformational for Ted, who had never given much thought to racism (and definitely didn’t go to Cambridge to be enlightened on that topic). In the course of a week, the conversations he had and the connections he made to people he would never otherwise have met proved transformational. Ted is now a full blown warrior for the DEI cause. He’s a great symbolic messenger to make the point that racism hurts everybody.

For instance, at one town meeting, Ted asked his peers (people like firefighters), “Why do you all have such long commutes to get to work?” The root cause was that housing prices were so expensive in town that people had to travel further to find something they could afford. Restrictive zoning legislation meant only the well-off could live in places that are conveniently located. The very depressed wages of white sharecroppers, in another example, were only tolerated because they were marginally superior to wages paid to Blacks. As Livingston relates, Ted came to realize, as a white person who was struggling, that the same structural conditions that affected people of color were also affecting less well-off, blue collar white people. “When he came to that conclusion, it became a passion for him to do something about it.”

As we discuss, there are whole books written about how racism inadvertently hurts everyone. One Livingston mentions is “The Sum of Us” by Heather McGhee in which she tells the story of how local communities literally filled in their public swimming pools, depriving themselves of the benefits of access, in order to prevent Black people from enjoying the same privileges. Most people would be better off if we have a more just and equitable society is the main conclusion.

Something I had not thought about before our chat was what Livingston calls this social pact – that less well-off white people would not have income or security, but at least they would have whiteness, which served as a sort of a salve on what might otherwise be considered untenable situations. Having bought into that social pact, it then needed to be defended, rendering the sentiment of “OK, we would rather not have a swimming pool than have to share it with those people who we are so much better than.” It became a false source of pride. That’s what Ted saw, and what outraged him so much was that he’d been bamboozled, his whole town had been bamboozled, by this narrative.

Racism resides in the delta

So we start off with “is this even a problem?” Many people in America don’t think that racism is a real problem, or that it has been resolved by now. Or that racism is only present in extreme acts, such as the killing of 9 worshippers at a church in Charleston in 2015. Or that racism requires a malignant intent.

The way Livingston defines racism, however, is that racism is present in the differences in how people are treated. In a small example, if a Black person were given a ticket for jaywalking, that might or might not be a racist act. The real question is whether a white person would be given the same ticket if they exhibited the same behavior. We need to think about whether people are seen differently, evaluated differently and treated differently in the same situation, just because of their race. Even if someone is, in fact, doing something wrong, the question of racism arises when a white person would be treated differently in that situation.

In real life, people walk through the world thinking they treat everyone the same because they don’t have the benefit of the contrast condition in which the same situation is replayed with a person of another race, say. But not so in the social science laboratory. In one controlled experiment, researchers compared the responses of recruiters to identical resumes which had exactly the same credentials, save for using the name Latisha, instead of Emily, or Jamal versus Gregory.

They found that the applicants were treated very differently. As the study authors note: “The results show significant discrimination against African-American names: white names receive 50 percent more callbacks for interviews. We also find that race affects the benefits of a better resume. For white names, a higher quality resume elicits 30 percent more callbacks whereas for African Americans, it elicits a far smaller increase.”

So racism doesn’t have to involve hatred, intent or membership in the Ku Klux Klan, it’s the practice of evaluating or treating people differently on the basis of their race.

Drawing a distinction between stereotyping, prejudice and discrimination

In one of the more interesting parts of our conversation (because to me it connects with solutions), Livingston draws a distinction between stereotyping, prejudice and discrimination, terms that many of us use interchangeably.

Stereotyping refers to a belief. “Blacks are athletic”, or “Asians are good at math” might be examples. These are cognitive factors.

Prejudice refers to a feeling, attitude or emotion. I like (or don’t) members of this or that group. These are not cognitive factors, they are emotional.

Discrimination is behavioral. It’s how you act, regardless of the stereotypes in your head or your emotional preferences. So how you treat people is where discrimination exists, or not.

Research has shown, which was a surprise to me, that these three qualities are only moderately correlated. What that in turn means is that you can have a positive attitude toward a certain group, as in “I like members of that group” but still discriminate against them, perhaps unintentionally. You can also have a negative attitude about a group but nonetheless treat them equitably.

This is one of the first keys to dismantling racism. By exhibiting non-racist behavior, interacting in a positive way with people who are from another background, research shows that it can go a long way toward eliminating negative emotions or feelings about people from that group. One of the biggest remedies for unconscious bias is positive contact. You don’t need to reprogram people’s beliefs. Focus first on promoting equitable behavior, and through sustained contact, the beliefs may well follow.

People forget that D E and I are equally important

We see this scenario all the time – some organization proclaims that they want to increase their diversity, so they go out and bring in a bunch of diverse talents, only to carry on exactly as they did before, without giving that person a voice, equal representation or including them in key decisions. The result? Diverse talent walks right out the door again, defeating the purpose of the whole exercise. As Livingston points out, plantations in the south were very diverse places, but they were definitely not ones of equality!

One of the problems with looking for cause and effect in real life is that you never really know what caused what to happen. You can have horrible, toxic behavior that leads to great outcomes (cue Harvey Weinstein) and honorable, well meaning behavior that leads to poor ones (cue the stunning innovation of the failed startup General Magic). My late colleague Kathy Philips did this fascinating research in which she set homogenous versus diverse teams to a creative problem solving task, where you could actually determine which teams did better or not. What she found was that the homogenous teams felt absolutely great about what they had done. They got together, got right into it, time flew, there was little conflict and they completed the task ahead of schedule. The diverse teams? Not so much. They struggled to understand one another. They had conflicting views. They couldn’t agree on priorities and it took longer to do everything.

The result, however? The homogenous teams did systematically worse on the creative task than the diverse teams. Kathy drew on neuroscience to explain this – being confronted with difference activates a different, more creative, part of our brain than when everything is just humming along, business-as-usual.

Learning requires discomfort. In fact, as Livingston points out, the learning zone is nestled between the comfort zone and the danger zone! If you stay in the comfort zone, you’re never going to grow (a point also made by Whitney Johnson, whose new book we’ll be discussing in a future Fireside Chat).

The difference between equity and equality

Livingston tells the story of a visit he made to attend a track meet at which his cousin, Terry, was competing. From the bleachers, he was outraged that the runners were set at different starting points in their lanes on the oval track. “I said, Look, they’re cheating – they’ve given everyone a head start over Terry!” Terry happened to be on the inside lane, and to Livingston’s eye, that looked unfair. His family members tried to explain to him that the runners on the outside lanes had to travel a longer distance, so the different starting points compensated for that, but he acknowledged, “at that time, I just didn’t get it.”

He draws an analogy to how people view equality – for many people, starting everyone at the same starting point is treating them equally, without regard for the distance they have to travel. Equity, on the other hand, is what the staggered start is trying to achieve. What equity does is create a level playing field.

Every other way of setting things up is “affirmative action for white males.” How else can you explain that 30% of the population (which is what white males are) holds so many – over 90% – of the positions of power and wealth in our society – from CEO’s to Presidents to you-name-it.

What’s needed is the commitment to the change first – and the strategies will follow.

Structures and systemic racism

In the book, Livingston outlines 5 structural causes of systemic racism that we could actually change if we mustered the resolve to do so.

1. Voting rights

2. Economic inequality

3. Public education

4. Criminal justice

5. Health care disparities

Company examples

One of the companies that Livingston cites as an example of taking action to make a real difference is Massport, the Massachusetts Port Authority. In evaluating bids, the company changed its criteria to weight diversity at 25% of the components necessary for a firm to succeed in doing business with it. As Livingston points out, before that, people simply used their existing network and processes to find contractors and other suppliers. “It isn’t that we were racist, its that we were busy!” one operator reported. After the new criteria went into effect, they had to do the work to broaden their networks and find diverse talent for roles they might not have considered before.

Quotes from The Conversation

- “When it comes to performing mental gymnastics most of us are Olympic Athletes.”

- “While many whites believe that color grants them no special privilege, almost no white person believes that the color of their skin is a burdensome cross to bear.”

- “If we summarize the origins of racism (and sexism) in a single word, it is power. It is both the desire to maintain power and the fear of losing power.”

- “A more secure and happy person is a more tolerant person. You can reduce prejudice simply by feeling good, calm, and secure.”

- “Racism occurs when individuals or institutions show more favorable evaluation or treatment of an individual or groups based on race or ethnicity.”

- “Prejudice is an attitude – a set of internal beliefs, feelings, and preferences. Discrimination refers to actual behaviors, decisions, and outcomes.”

Dr. Livingston’s Website

- Website: https://robertwlivingston.com/

What to do next

As the book suggests, a great next step is to engage in conversation. Conversation is one of the most powerful ways to build knowledge, awareness and empathy and ultimately to affect change.

To end on an optimistic note:

Racism is a solvable problem.